In brief

Every community and every organisation is shaped by norms, assumptions and rules. They condition our behaviour, determine what is and is not permissible, and mould our relationships. Here, David Robinson discusses changing our permissions; a theme that we explored in more depth during an in-person get together of 120 relationship-centred practitioners in Birmingham, July 2024.

Whether inherited, imagined or deliberately designed, Unspoken Conventions, Imaginary Rules and Real Rules influence our social behaviour, and shape the extent, the content and the quality of our relationships with one another.

Unspoken Conventions affect how we feel about the way that we and others should behave. They shape the behavioural norms to which we mostly conform

We model the Unspoken Conventions and we pass them on. Over time, they evolve into what we assume to be required. The convention becomes an Imaginary Rule

Every organisation or society also has Real Rules. They set down what we know to be permitted or forbidden. They are explicit and enforced by sanctions

Taken together, Unspoken Conventions, and Rules both Real and Imaginary, set the permissions for our shared lives, condition our behaviours and shape our relationships. To change how we live together, and to put relationships first, we need to change our permissions.

Unspoken Conventions

Whenever I wear my West Ham scarf people talk to me. I say “people”, it’s mainly men but not necessarily West Ham fans. Followers of other teams are just as likely to start the conversation, and not only in east London. I had a lovely chat with a lapsed Luton fan on Doncaster station a few weeks ago.

Isla, my baby granddaughter, casts a similar spell. This time it’s usually women who peer into the buggy and say “how old?”

It’s as if the scarf and the baby are flashing signs that say “Normal rules do not apply. Let’s talk. Maybe about football. Maybe about babies. Or maybe about something else entirely”

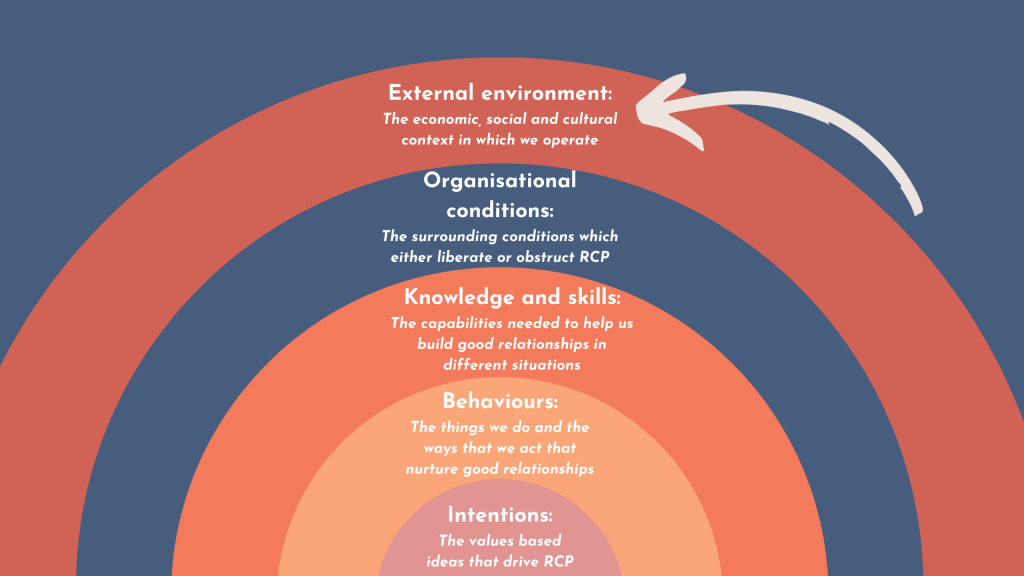

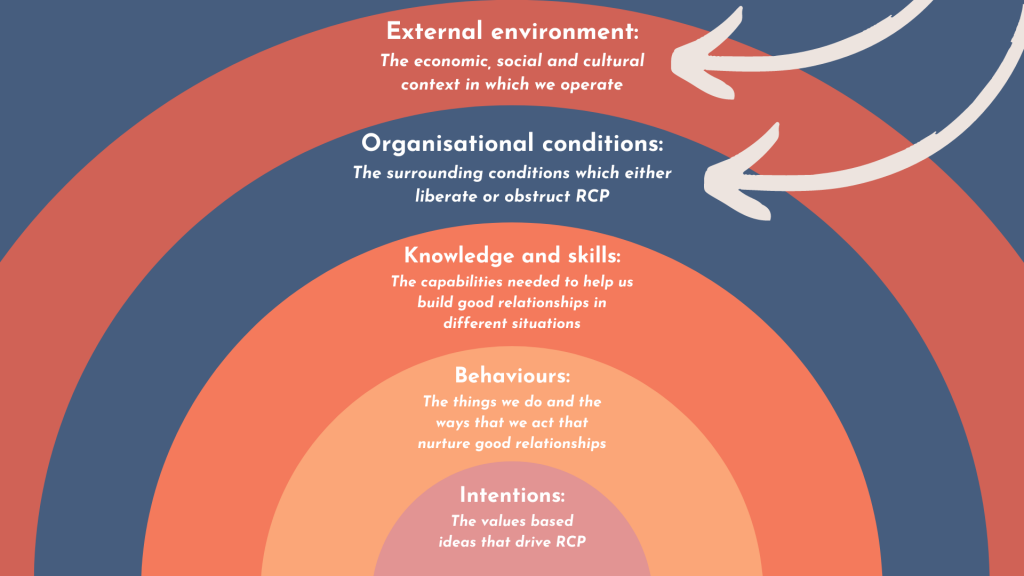

In our work on understanding and explaining relationship centred practice we talk about the economic, cultural, or social influences which either liberate or obstruct relational practice. With the most minimal tweak, Isla and the scarf disrupt those conditions.

The permission of snow

Something similar happens to us all when it snows. Overnight, as the conditions change so do our permissions. We talk to neighbours, to fellow travellers at the bus stop and to people at the shops. Speaking to people we have never spoken to before is no longer strange. In fact it would be rude not to. We call it the permission of snow. Big national sporting occasions, even royal weddings, can trigger a similar response.

Lockdown, of course, changed everything. Perhaps counter intuitively it was during those dark weeks four years ago that we re-neighboured, communities came alive, and we spoke to one another. We followed these shifts in social behaviour on the Relationships Observatory and told the story in The Moment We Noticed. This comment was typical “ I’ve never really been a joiner but I popped a note through the doors round the block. I’m shopping for three people now. It isn’t much but it’s something”

“The better angels of our nature were suddenly flapping everywhere” wrote historian Professor Peter Hennesy. A Duty of Care 2020. Covid changed the permissions and we, perhaps not permanently but in large numbers, changed our behaviour.

Deliberate disruption

There are no laws that outlaw interaction on the street unless it snows, or forbid conversations between men who aren’t followers of football teams.

The permissions are unwritten codes and unspoken conventions. They vary across communities and regions. Crucially, when the context shifts, the convention is disrupted and behaviour changes.

Snow and babies in buggies do it naturally, so did Covid and the lockdown, but badges like “Happy to Chat”, Street parties, even Street furniture and Tippees in unexpected places, are all intentional initiatives that can work the same magic.

In their different ways each one draws attention to the unspoken, perhaps often unnoticed, conventions which underpin our customary behaviour. They challenge us to see things differently and to make choices. We may decide to carry on just as before, but even the most minimal disruption reminds us that conventions are just that: conventions, not laws. The permissions are voluntarily applied. There are other ways of behaving and we are free to choose. Whilst natural occurrences may do this accidently we can also replicate the positives with care and intention.

What do you think?

- What are the Unspoken Conventions in our workplaces and systems which help and hinder our ability – and permission – to put relationships first?

- We behave differently in different places. What do we know about places that encourage and support good relationships? What part does the built environment play? And what are the implications for how we think about and use spaces and places?

- How else can we help one another to change the permissions and get better at putting relationships first in our communities, organisations and systems?

Imaginary Rules

When I think about Imaginary Rules, I think about a conversation I had a few years ago with a friend who is also a nurse. I was telling her about the comfort my father had derived from the consultant who sat on his bed. I had been with him at the time and seen how the conversation changed when she sat down and took his hand in hers.

“I am afraid that we can’t sit on beds” said my friend “it’s a rule”.

“Whose rule?” I asked. “The hospital trust, the ward manager, the RCN, the NHS?”

Neither of us knew.

I understand that there may be sensible reasons, perhaps to do with hygiene or infection control, why it is generally preferable to not sit on beds but, if so, this is a guideline not a rule. Surely risks must be balanced . If I was terminally ill I think I would prefer to be comforted and reassured, to feel cared for, than to know that even the most minimal danger of additional infection has been anticipated and eliminated. I am, after all, already dying. Many clinicians seem to be similarly concerned about “rules which diminish the joys of life (in hospital) where joy is already in short supply“.

It seems odd that a highly experienced nurse can be trusted to manage drugs that will kill us if not administered with the greatest care and proficiency, and to calibrate and control machinery that is literally keeping us alive, but not trusted to make a judgement about whether or not to sit on the bed.

“But still, I wouldn’t do it” my thoughtful and caring friend concluded “Just to be on the safe side”.

Organisational conditions and the external environment

Whether the sitting on beds rule is real or imaginary, foolish or wise, it has become one of the Organisational Conditions that either liberate or obstruct relational practice – the fourth layer in our model. This, in turn, is at least partly because clinicians, and the managers around them, are influenced by the External Environment, the outer layer – public opinion, media coverage, political comment.

Changing the Imaginary Rules is often as much about questioning this external context as it is about challenging the organisation. Neither is easy but both are important because the “just to be on the safe side” mindset is an insidious disease.

Imaginary Rules, sustained by risk parameters decoupled from reasonable judgement, squeeze out the human touch and suffocate relationships, not only in the NHS but across our public services.

“Do no harm” is the first principle in the Hippocratic Oath capturing the essence of medical ethics. It might equally apply to other public services. Entirely anecdotally but in many conversations over recent years, I have learnt about big organisations (and occasionally some quite small ones) that are riddled with untested assumptions and Imaginary Rules. The protocols are upheld in good faith, but any good they do is often outweighed by the opportunity cost, if not by real damage.

Mark Smith, the director of Public Sector Reform at Gateshead Council, works on applying a “Liberated Method” to public services in the North East. His work is based on just two absolute rules – “do no harm” and “stay legal” – and on five principles which “guide decision making”. The team found that roughly two thirds of what they now do differently was not previously prohibited. It was “current preoccupations” which prevented them from seeing the value of “operating on the basis of relationships which can absorb variety rather than processes which cannot” .

The Liberated Method is not a quick fix. It is about understanding the deep codes that determine how an organisation thinks and behaves and changing the soul, but the longest journeys begin with a single step. It may be that the first and most useful thing we should do when encountering a rule that inhibits relational practice is to ask a simple question: is this really prohibited, or is it an imaginary rule?

What do you think?

- Does this idea of Imaginary Rules resonate with you? What do they look like in your world?

- What are the factors, within the organisation or within the wider environment, which support the rule or get in the way of challenge and change?

- How can we help one another to spot them, to contest them and to change our permissions?

Please join us in Birmingham to share your experiences.

Real Rules

There are many areas where organisations and communities need real rules and the sanctions to uphold them. It might be possible to change them in due course but in the moment, they are non negotiable. Safeguarding seems like an obvious example. Even here, however, there can be a case for defining the scope for judgement.

I was talking with head teachers a few weeks ago about the rules around working with children in primary school, particularly in early years. Everyone stressed the vital importance of clear protocols on every aspect of safeguarding “but” said one “if my five year old is crying in the playground, I want someone to pick him up and hug him”.

Mark Smith again: “Regulation and inspection have a role to play but are often predicated on the idea that quality can be inspected. What it actually does is create a fear of straying outside a safe bandwidth of options or methods and cannot absorb the variety that is people and what matters to them”.

Russ Bellenie is the Principal Social Worker with Barking and Dagenham Council. He talks about “hopeful disruptions” as part of their approach to developing a “radical, relational service”. He cites the example of a colleague who took one young person to see a favourite band.

Inappropriate? Risky? Irresponsible?

Certainly the trip was outside the normal rules but it was very carefully considered. They did a risk assessment. A special budget was granted. The head of service signed it off. And it worked. Sharing this moment of connection was a breakthrough in a relationship that had previously been difficult and unproductive.

No one would want to take chances with safeguarding but perhaps even here there is room for judicious exceptions?

Systems are made by human beings. Even Real Rules can be thoughtfully challenged, exceptionally suspended and occasionally re-made.

Organisational conditions and the external environment

Some years ago my wife had cancer and was assigned an expert nurse called Anne. The nurse stays with the patient throughout their treatment. From surgery to chemo and radiotherapy, Anne was a constant and reassuring presence, kind, knowledgeable and highly skilled. At our first meeting shortly after diagnosis, she gave us her personal phone number and told us that we could ring at any time. It struck me as an extraordinary thing to do. Obviously, she had other patients. They would all be treated the same. How could she possibly cope?

Many long months later when my wife was discharged we told Anne how impressed we had been by this selfless offer. “You must be troubled day and night”, I said.

“No”, she said, “it doesn’t work like that. We give the number to reassure. Patients feel held, trusted, cared for at a desperate time. Now and then we talk about our lives as well as theirs. They care about us. And they give back the respect that we give to them. People very seldom ring out of hours because they think I won’t trouble Anne now. She will be having tea with her daughter.”

Anne disrupted the unspoken convention. It’s not what nurses and doctors normally do. Some might think it risky, but apparently it isn’t. We assumed that it broke the rules, but we were wrong – she was following the protocol established across the team. Maybe there was once a Real Rule? Had the team obtained permission to change it? Or was the rule Imaginary?

Life is seldom as simple as a neat model or a short blog. Out in the real world, Conventions, Imaginary Rules and Real Rules come muddled up together, but Anne’s impact on our lives could not have been more immediate or more positive: A newly minted, professional relationship became a good relationship, a real one. Still professional but demonstrating, with one bold, big-hearted gift, the behaviours and the intentions that underpin relationship-centred practice and beat at the heart of our model: reciprocity, kindness, trust, presence, vulnerability and more.

Anne changed the permissions. She put relationships first. She changed how we felt, how we thought and how we behaved. And at a particularly difficult time for our little family she improved our lives.

We need to do it more.

Permissions Game

The Permissions Game invites you to explore the rules and norms that influence how we work and what we prioritise via a series of engaging scenarios. Gather your team, download the pack and press play!

Relationships Case Maker

Few people argue that relationships don’t matter, but many feel they don’t have the time, capacity or permission to prioritise them. This Case Maker assembles the evidence base for putting relationships first, describing why relationships matter, what great relationship-centred practice looks like, and how it could make an impact in your context.

More from the blog

A birth and a knock to the head

When we’re unwell, how does the compassion that healthcare workers give (or fail to give) shape our experiences and health outcomes? In this blog, Rosa explores these questions, and shares two personal experiences that have shaped her thinking - (accidentally) giving...

Four signs: Love is the running to strangers

In this short, personal blog, David reflects on the power of kindness, and runningthrough fire.Early one morning "I’m leaving today." "Leaving?" I said, puzzled by the early morning call and pushing back sleep, "Where are you going?" "Leaving," she said slowly,...