Key Concepts | What we mean by relationship-centred practice

Relationship-Centred Practice puts relationships first. It unlocks potential and meets need by positioning meaningful and effective relationships as the first order goal, both an end in itself and the means by which other goals will be achieved (like better health, stronger communities, greater job satisfaction)

We think Relationship-Centred Practice is characterised by empathetic behaviours such as positive listening, active collaboration, a commitment to continuity, kindness and mutual trust. There is a shared sense of purpose and also of agency – “we can do this together”, capacity for challenge, for holding tensions alongside compassion and forgiveness, a focus on assets rather than deficits and sufficient versatility to adapt the practice to the individual rather than fit the individual to the programme. It is informed by experience, but not scripted. The most effective relational practice is not enforced from without. It is compelled from within, willing and dynamic.

Relational working is more than an instinct; it is a craft and we need to learn how to do it well, and how to create the conditions in which it can become embedded.

Relationship-centred practice is most obviously associated with a set of behaviours – e.g. active listening, patience, empathy and active collaboration – and with ‘frontline’ roles – like healthcare practitioners, social workers, community workers. But these behaviours are unlocked and enabled – or constricted and disabled – by the conditions in which we each operate.

For relationship-centred practice to become widely embedded, we all need the knowledge and skills to build relationships, and we need to be supported by processes, protocols and norms which liberate relational work.

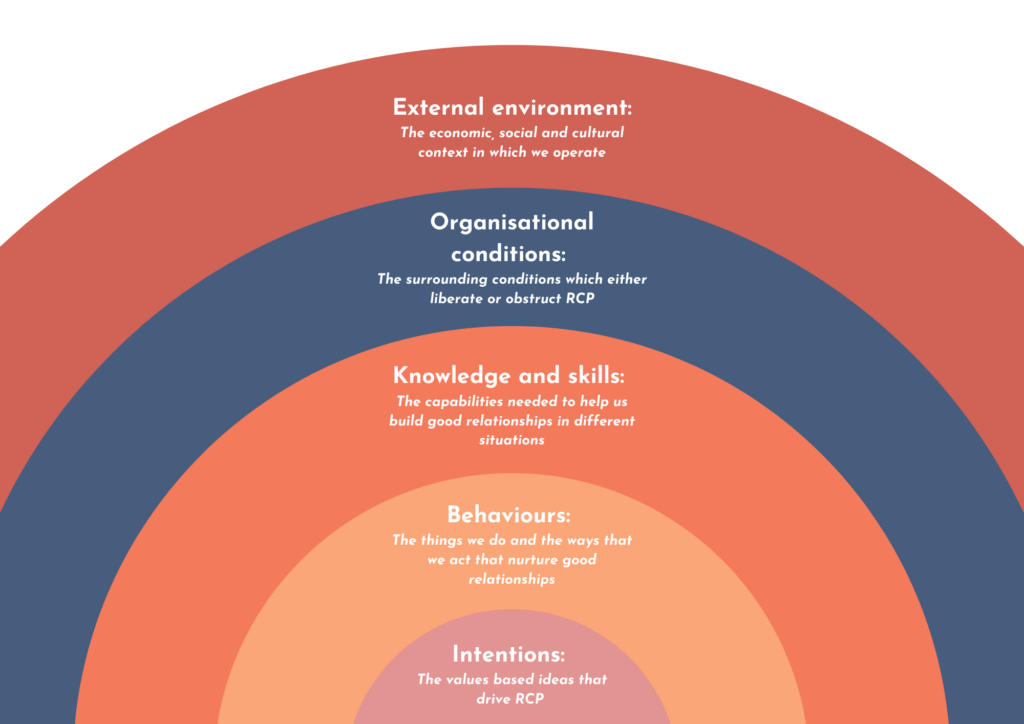

Layers of Relationship-Centred Practice

Underpinning intentions

We think that underpinning RCP is a set of values-based ideas or commitments. We think these are transferable across sectors, specialisms and approaches and without which a commitment to putting relationships first cannot be realised. We think these principles are something along the lines of….

Characteristic Behaviours

Emerging from this set of principles is a set of behaviours that characterise RCP. These behaviours are an expression of the principles that sit at the heart of RCP and are the observable components of RCP. Some of these behaviours might be transferable from role to role, and from organisation to organisation, others might be more specific to certain situations.

These behaviours include things like….

(For a profession-specific, lightheared example of relational behaviours enacted by great teachers, take a look at this list put together by the late Sir Tim Brighouse)

Knowledge and skills

Enabling these sorts of behaviours are a set of competencies; knowledge and skills which enable us to build relationships in different situations and contexts. Some of these competencies are widely applicable; skills such as active listening, others more specific to certain situations, such as conflict transformation.

Enabling organisational conditions

Wrapping around all of these is a set of enabling protocols which can either inhibit or enable relationship-centred practice. Without the appropriate protocols and permissions embedded in organisations, systems and structure, the relationship-centred practitioner will always be a maverick, dependent on managers “turning a blind eye”. In this context it is very likely that the approach will be abandoned, and good work lost, when individuals move on.

To build the sort of society that we dream of requires an enabling environment. We saw a glimpse of that environment during the early stages of COVID and are working with the Relational Councils Network to make it a permanent fixture.

External environment

More key concepts…

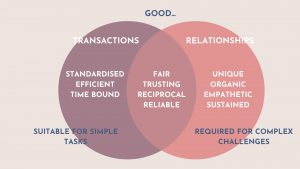

What we mean by good relationships

Characteristics of good relationships, and how they differ to good transactions

Why putting relationships first makes a difference

Stories and statistics that help make the case for putting relationships first

Thank you

, am enjoying the website and language

As a relationship cantered initiative here in Ireland I wonder could we use your diagram .depicting the layers of RCP please

We Woukd of course credit you if you agree

Hi Maeve, lovely to hear from you. Yes, please do!