Mutual aid was driven from the ground up but flourished with appropriate support from local councils. The UK response to refugees arriving from Ukraine was led from the top down but could only succeed with local engagement. What can we learn from this approach to the Ukraine refugee crisis? How do the top down, bottom up approaches play out on the ground? Where do they converge, what are the strengths and weaknesses and how do we apply the lessons now?

In this blog, we share insights from our session on 12/7/23 in which we heard from three fantastic speakers: Neil Denton, Professor in Practice at the Institute of Hazard, Risk and Resilience and Co-Founder of the After Disasters Network, Paul Morrison, former Director of Homes for Ukraine, and Professor Kate Cochrane, Head of Resilience for NHS Highland.

Resilience is relational

Neil Denton, Professor in Practice at the Institute of Hazard, Risk and Resilience and Co-Founder of After Disasters

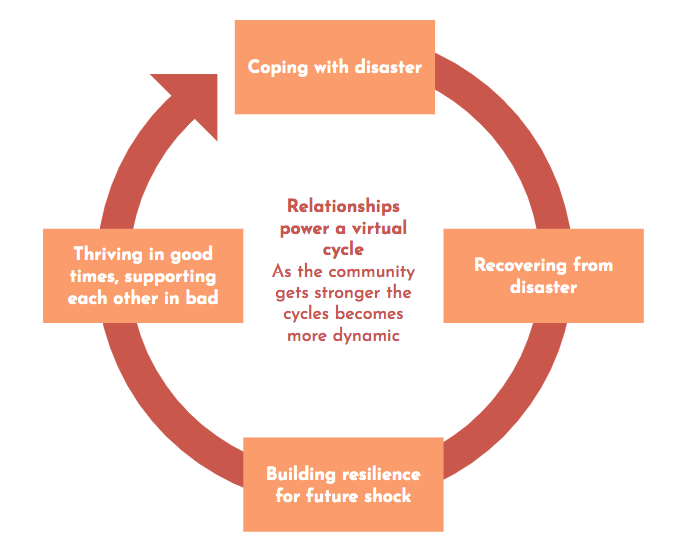

Strong relationships not only enable us to make the most of the good times, but to weather the bad.

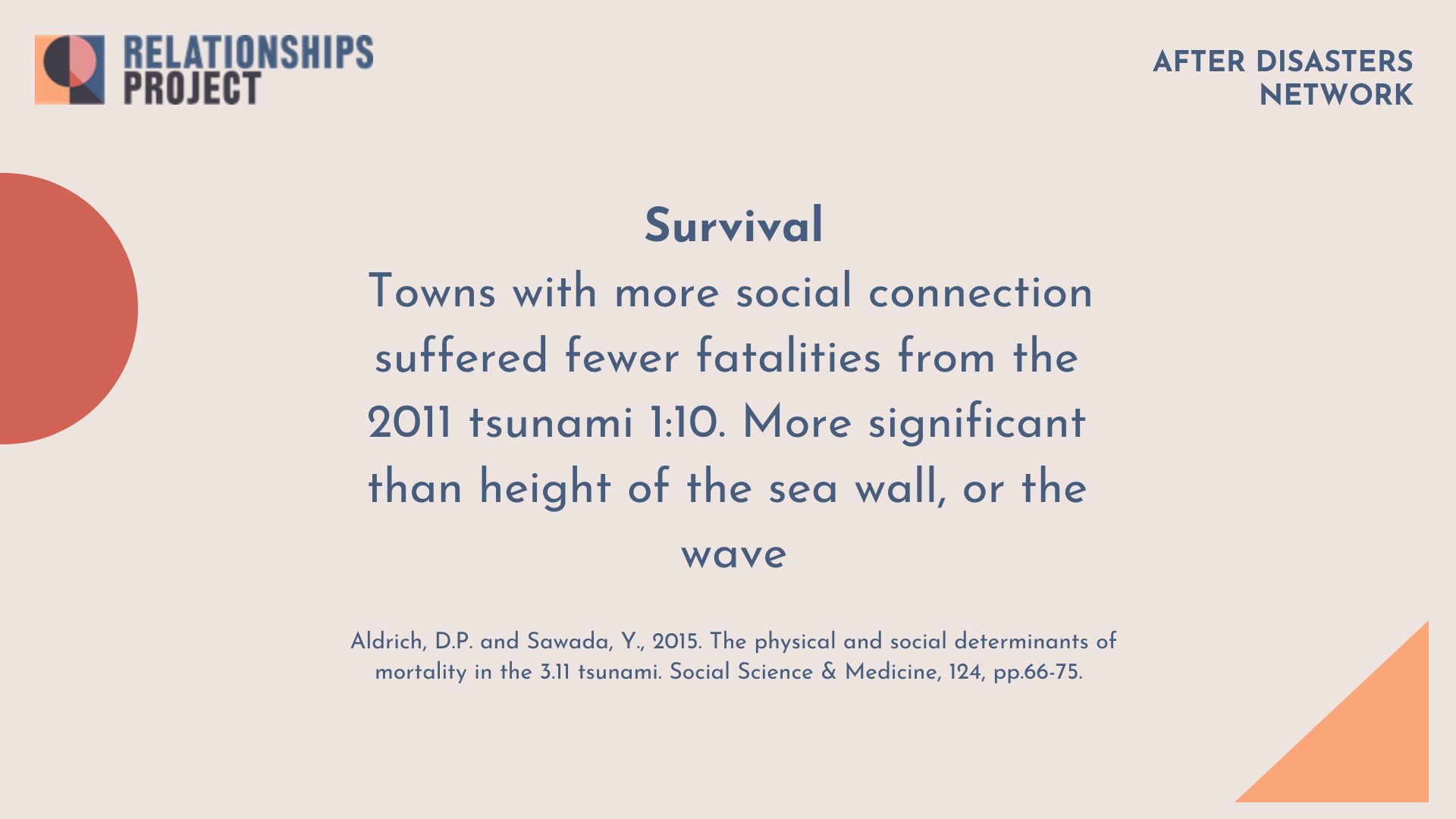

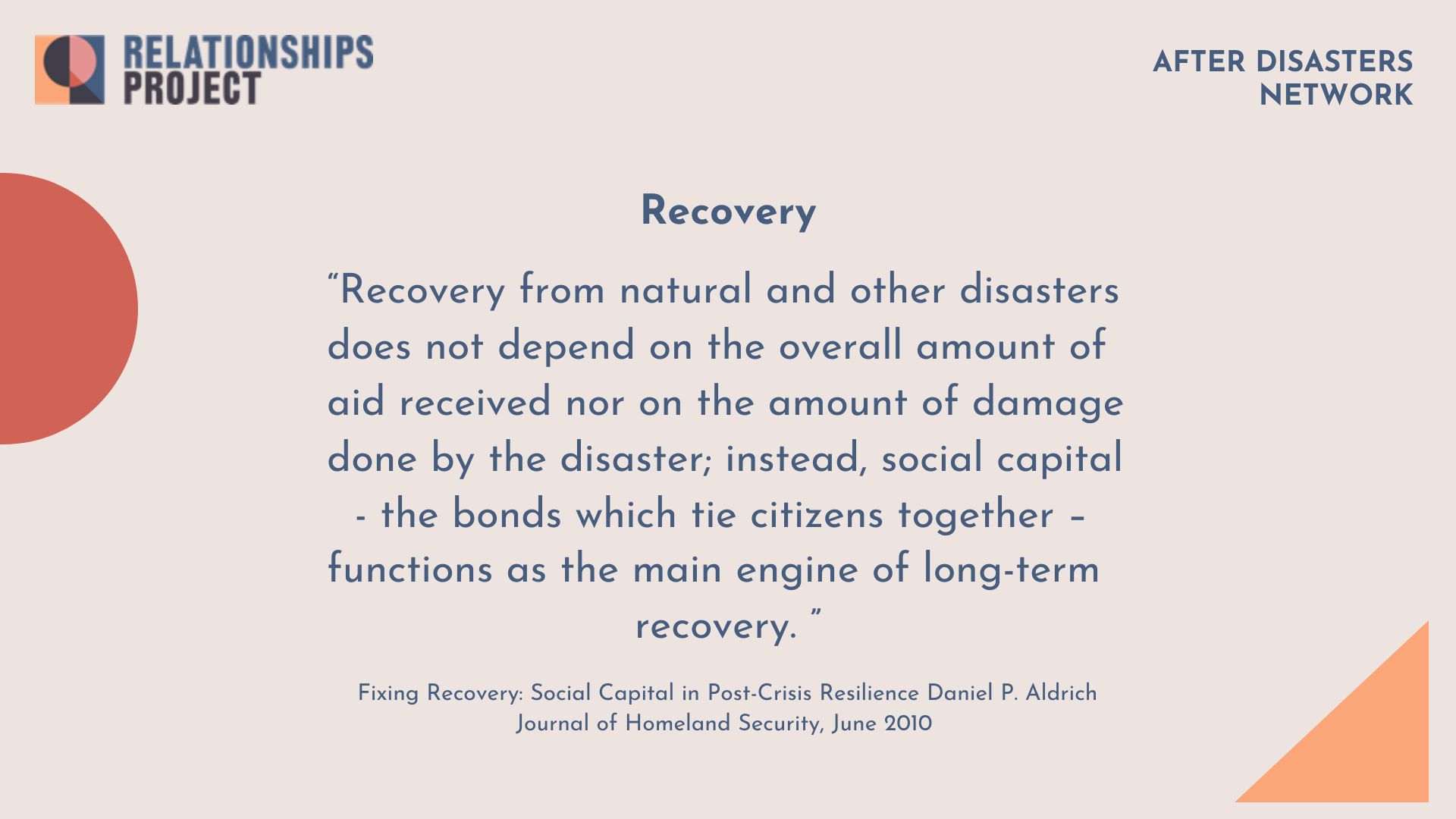

Research by Daniel Aldrich and co shows, with almost unbelievable certainty, that strong community relationships are a more significant determinant of fatalities in the wake of natural disasters than physical defence structures like sea walls.

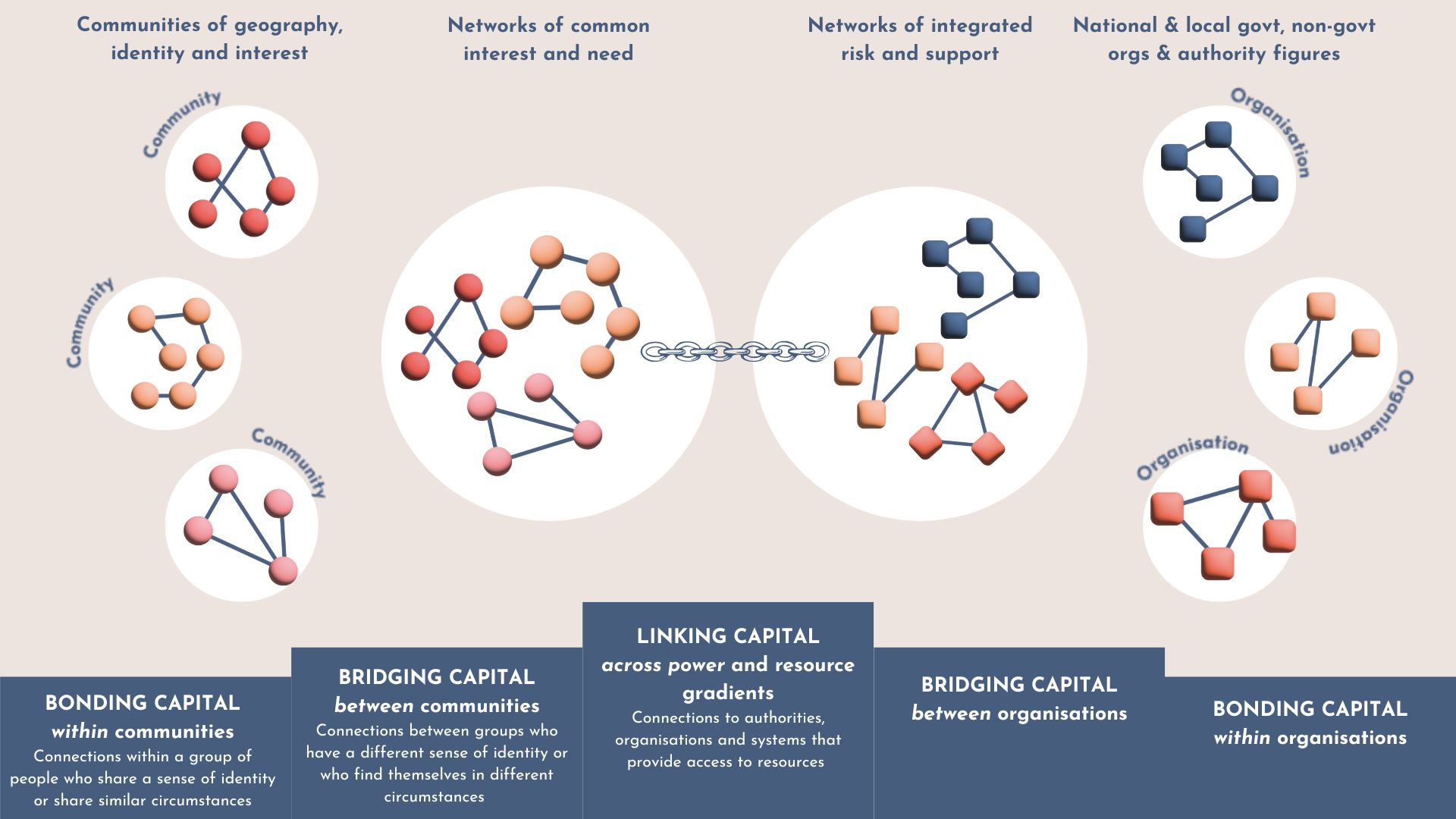

At first glance, this might seem surprising. But communities that are bonded and linked know who needs support evacuating, who to call for what, and who has access to what. Communities who know one another well, and have good relationships with government and non-government organisations, rally together in a more effective and efficient response.

Homes for Ukraine

Paul Morrison, Chief Executive of the Planning Inspectorate and former Director Homes for Ukraine, Ukraine Humanitarian Taskforce

Paul shared his experience of moving from delivering large scale transactional functions of the Home Office – like issuing visas – to managing the much more complex challenge of welcoming refugees, first from Syria and, more recently, from Ukraine. He reflects that the complexity of this challenge required a much more collaborative, relational approach.

That collaboration began in meeting rooms involving civil servants and large organisations like the Refugee Council and local government (referred to as organisational bridging capital in the diagram above). But, drawing inspiration from a resettlement programme in Canada based on community sponsorship, Paul and his team began to develop an approach which engaged communities in the response (building linking capital).

The Homes for Ukraine programme saw the government take a much lighter touch approach to resettlement than it has ever previously done. The state did basic checks on hosts, but beyond that offered very little in the way of interference. The policy simply stated that if you’re a Ukrainian refugee with a UK host and neither of you are criminals, you can have a visa.

Crises are about people

Kate Cochrane, Head of Resilience for NHS Highland, Professor in Practice at Durham University’s Institute of Hazard, Risk and Resilience, and Co-Founder of After Disasters Network

How we learn from crisis

A crisis is many different things. It can be a sudden or emerging event. It can be natural or man made. It can be acute or chronic. When we talk about disaster management we tend to grab at structure charts. But crises aren’t about structures, they’re about people; about impact on real people.

When learning from crisis, Kate and her colleagues ask three questions:

- In responding to the incident, what didn’t go well or as expected?

- What went well or better than anticipated?

- What recommendations and actions do we need to take forward?

And through the process of learning – the approach to learning – relationships are built. In engaging with communities, Kate and colleagues are trying not just to understand and learn, but to strengthen relationships between community and authority (linking capital) and create a landing space for recommendations.

Done well, working relationally is extremely powerful. But done badly, it can set us back decades”. When we’re building relationships of trust with communities we need to do so with care and with compassion. Power imbalances must be recognised and acknowledged. We ignore them at our peril

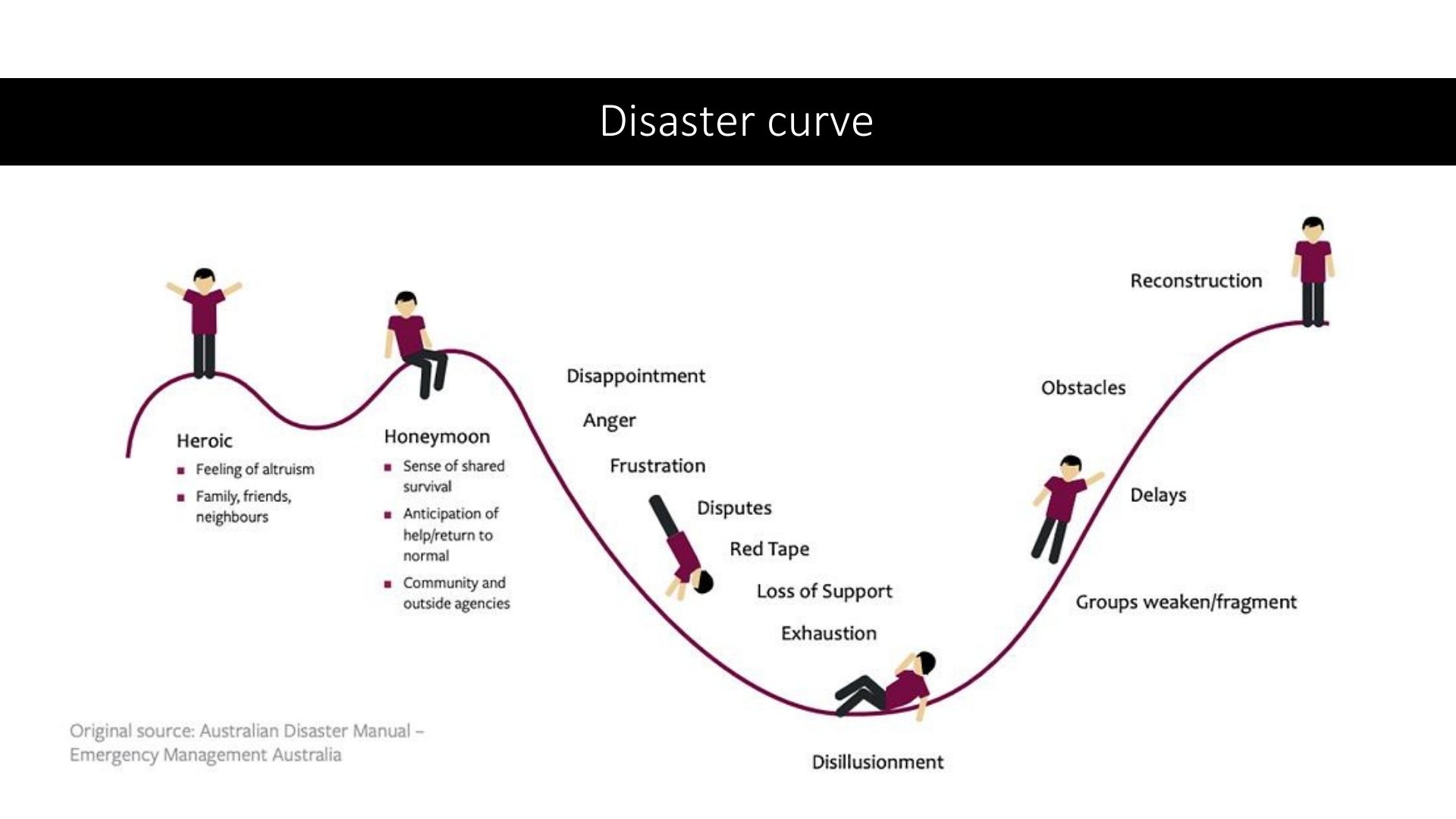

How relationships change throughout crises

At the start, we typically see a hyper bonding. This is soon followed by debonding – the loss of connection in the chaos that follows. Debonding is commonly followed by re-bonding: the creation of new bonds with sharp boundaries. New communities form with ingroups and outgroups. This can make it difficult for those with helpful resources to break through. We see scapegoating and blame.

When deliberate attention is paid to building community cohesion- in times of non crisis as well as in the aftermath of crises – the recovery trajectory is much quicker.

Comments on trust and power

Much of the group discussion revolved around the topic of trust, emphasised by Paul in his description of the Homes for Ukraine programme and built on by Kate in her reflections on working on multiple disaster responses. Questions of power, and how trust and relationships can grow in the context of imbalances of power, quickly arose.

Trust is truly catalytic. To build trust requires an unending curiosity. Why is someone saying what they’re saying? And why am I reacting the way I’m reacting?

To build trust, you need to set the relationship up in the right way. You need to legitimise differences in views, be clear about what you can and can’t influence, follow up with action and do what you say you’re going to do. Be clear and honest about the unwritten contract on which trust is based

We – as experts in disaster and people in positions of power – need to couch the hazard and risk in ways that don’t scare communities, without dumbing it down so much that we lose trust. There are some things that I, as someone in a position of authority, cannot share. This is not because I don’t trust communities, but because there’s systemic distrust. During disasters I don’t have time to build trust. I need people to ‘do’. So I invest lots of time in virtual coffees between disasters to build that trust

Imbalances in power can fuel distrust. As a figure of authority you need to be honest about your role and the power that you hold whilst being careful not to hoard power. The more people feel you are sharing power – whether that power is in the form of information, voice, relationships or something else – the more they will trust you

Strong bridging relationships enable us to disagree well. They’re a strong foundation on which it’s harder for trust to be shaken

[For more on how to build bridging relationships, take a look at the Bridge Builders’ Handbook]

A resident is more likely to trust someone that they know – a neighbour, their hairdresser, their faith leader. LBBD have been exploring how those networks of trust can be embedded in their cost of living response, asking the question: how do we put resources where trust already lies?

[For more on relational responses to the cost of living crisis, head here]

Recommended reading

The Sense of Connection

In this report, we draw on the expertise of the After Disasters Network in the crafts of disaster recovery and conflict transformation, and weave this together with all that we’ve learned from our own network about community development.

We take stock of the past two and a half years of Covid and look ahead to a long, hard winter. We share some steps that we might take together as we navigate the road ahead and we invite you to join us in understanding how to support strong and connected communities.