In brief

Ofgem confirmed the increase in the energy price cap on Friday August 26th 2022. We now know that, without substantial help, galloping fuel bills, combined with inflation, will push 45m Britons into fuel poverty by the end of the year.

David Robinson explains why this crisis, and our collective response, must be a turning point. More than “just for now” crisis management, we need to reimagine and refound.

Many people have been standing on the beach staring out to sea for a long time this summer. We’ve seen the great wave coming. The first big roller, the Ofgem announcement, hit the shore on Friday. There is blame and discord: “who didn’t build the defences high enough and strong enough?”. The siren voices are a little louder and more numerous today but even now there is a curious still. What to do and who to do it?

In another place and at another time, Daniel Aldrich and others showed that the communities with the lowest death rate and the fastest recovery following the 2011 Japanese tsunami were not those protected with the highest sea walls but those connected with the highest levels of social capital.

What was true of the disaster in east Japan in 2011 will be equally true of the metaphorical storm now breaking in the UK.

It will be social capital – relationships – that will determine our experience of the cost of living crisis this winter not because inflation and fuel prices and low wages aren’t catastrophic but because, when disaster strikes, it is the behaviour of the people closest to us that has the most influence on the impact.

This might include the acts of kindness and solidarity that characterised the response to lockdown in many communities and also the kind of collective economic action that was so vital in many communities during the miners strikes of the 1980s – community-led coops, collective buying schemes, local support for local providers. In his 2020 History Workshop, Diarmaid Kelliher notes that this was relationship-centred economics in action, enabling whole communities to survive without all their usual income and even to generate benefits that lasted long after the strike were over:

It was the experience of those twelve months that produced the sense of community in the places where they lived and worked

This isn’t to diminish the urgent demands of the Cost of Living Alliance, the Enough is Enough campaign and others for immediate support and for fundamental reform of the systems and structures that have forced so many people into the eye of the storm. Rather, it is to say that the necessary change for the long term is even deeper. It is about more than political and economic systems. It is about how we live together.

The shifts in behaviour

We were on this beach, uncertain and afraid, at the start of the banking crisis, anticipating austerity, and again a little under three years ago squinting at Covid on a distant horizon. We learnt in 2019 that different, pro-social behaviours were needed to cope with the onrushing crisis. We needed to reimagine our protocols and urgently refound our structures and systems.

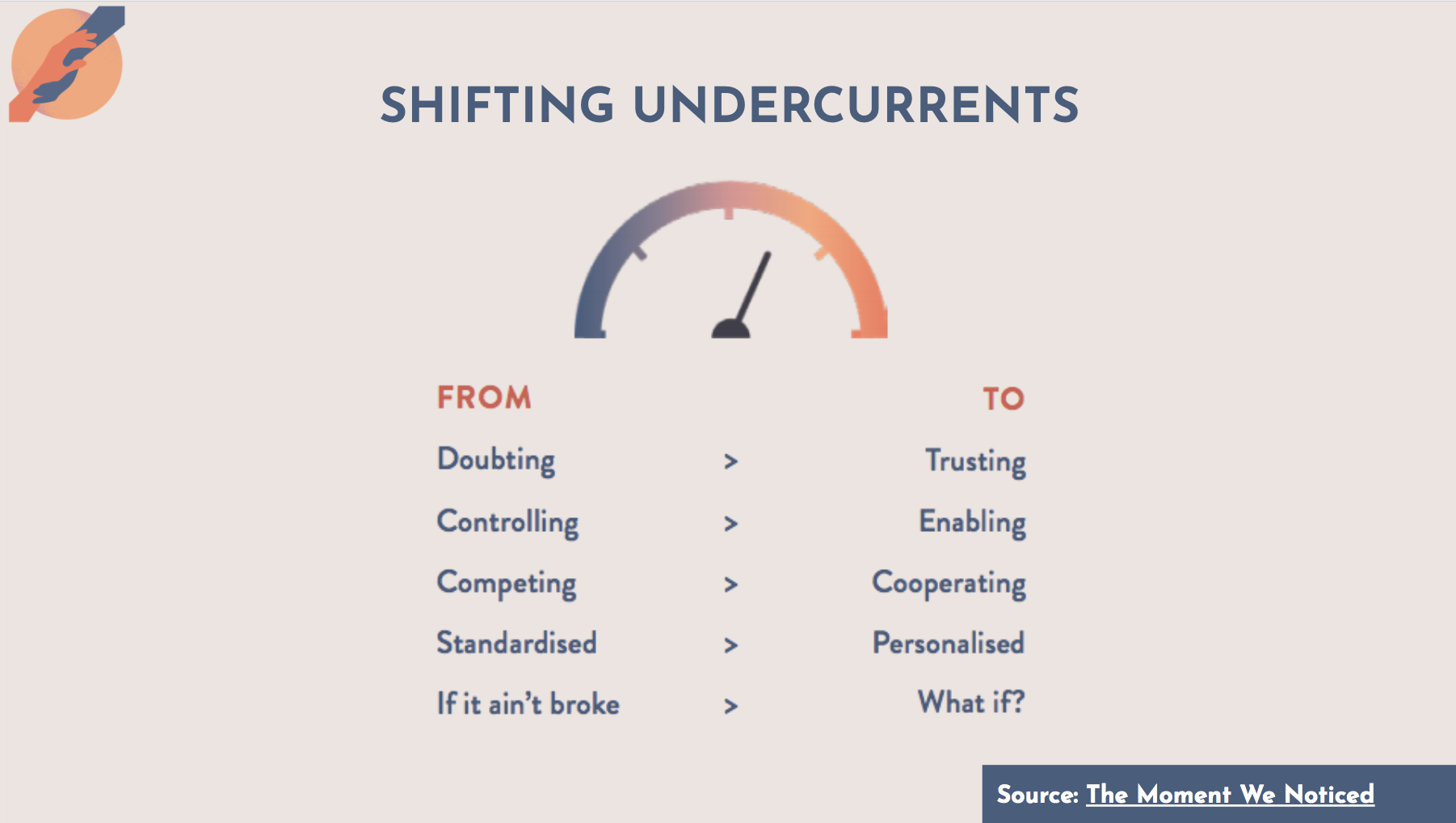

In The Moment We Noticed we reported on the first 100 days of the pandemic and noted how five major shifts in behaviour occurred in organisations and systems, large and small, public, private, and in communities. Those who moved furthest and fastest in these directions were most effective.

Thriving in the future

To stumble from crisis to crisis, seeing them approaching but not learning from past experience and preparing appropriately, would be foolish at the best of times. To continue to behave in this way when we know that the multi-faceted climate emergency is just beyond the sky line, is insane.

Making do and mending, tweaking old systems, inventing special “just for now” initiatives may be understandable, even necessary, responses to a breaking emergency but they wont be enough, even in the short term, if they aren’t underpinned and subsequently embedded, by a deeper revision of our relationships with one another.

We won’t meet the challenges of the next year, let alone of the next generation, with a continuing approach to our shared lives that is bureaucratic and codified, defensive, distrusting and fearful, transactional and centralised and impersonal.

These are the behaviours of the society we have built. They are not the defaults that will enable us to thrive in the future.

Working differently, working relationally

Writing in the Guardian on 19/8 Aditya Chakrabortty described the mobile shop run by Well Fed – a community business that manages to undercut Iceland. Amongst other activities, they also do Meals on Wheels and ready meals for £2 and a local housing association now provide Well Fed lunches for all staff. The free lunches save Clwyd Alyn employees about £100 a month and, as one employee noted, are so much more social than a sad sandwich on the job.

Working differently, working relationally, Well Fed addresses food poverty with a community-led approach that is commercially savvy, socially driven and plainly effective. It is a single, relatively small example but it could work almost anywhere and be run from any, or all sectors. I heard recently, for instance, that a medium sized business and a large hospital are both considering something similar. Key principles of the Well Fed approach show the way – humane, relational, local, pragmatic, sustainable.

(For more examples of relationship-centred organisations and businesses, take a look at our case studies)

Our greatest natural resource

The relationship between citizens and the state, or the relationship between citizens and the market? These have been the duelling orthodoxies tussling for primacy and constraining public policy in the UK for the last seventy five years. Now the UK has entered an era when neither serve us best.

It is time to focus instead on the primacy of relationships between citizens. They are our greatest natural resource and should be at the centre of public policy and practise, designed in rather than, as too often now, designed out

Starting here begins a new conversation. In some corners of the state it is as much about what not to do as it is about what to do, but this is a plea for different government not for smaller government, for a state that enables, encourages, trusts and supports its own staff as much as the communities it serves, for more money and more power diverted to more people to build and sustain meaningful and productive relationships, effective and stronger communities.

This will look different in different places but the impacts will be similar. In his most recent work Aldrich et al plotted recovery levels from Hurricanes Katrina and Rita and compared the relative impacts derived from backing social as opposed to physical infrastructure and from local rather than state-wide policies.

The social and the local, they concluded, is consistently better for long term recovery.

Like the pandemic before it and the collapse of the banks in 2008/9, the cost of living emergency will soon be habitually described as “unprecedented”. So it is in all its specifics. Just as Covid was a once in a generation public health crisis demanding an exceptional public health response, the crisis this winter is economic and the immediate solution will be financial. But to focus exclusively on the surface, however alarming it may be, is to overlook the deeper currents and so ignore the longer term.

Humanitarian crises, past, present and future, call universally for a humanitarian response.

Seizing this year, this crisis, for a fundamental, sustained shift towards a world that is permanently characterised by kindness, solidarity and trust, a world that was briefly prefigured in the early days of Covid, would not be without risk but how much better would it be to get the right behaviours wrong every now and then, than to hobble on, getting the wrong behaviours right over and over again.

If not now, when?