In brief

This month, the UK government announced a huge public rollout of AI. If the plans embrace relational offsetting, it could allow us to prioritise human relationships where they really matter. Our hope is that 2025 will be the year when relational offsetting becomes the preeminent tool for developing and managing public services.

In this blog, we outline the purpose of offsetting, explore some of the processes that might enable it, and explain why understanding and promoting “the art and the science” is more important now than ever before.

We’d value your support in developing these ideas. Please share any thoughts, questions or builds in the comments, or with david@relationshipsproject.org.

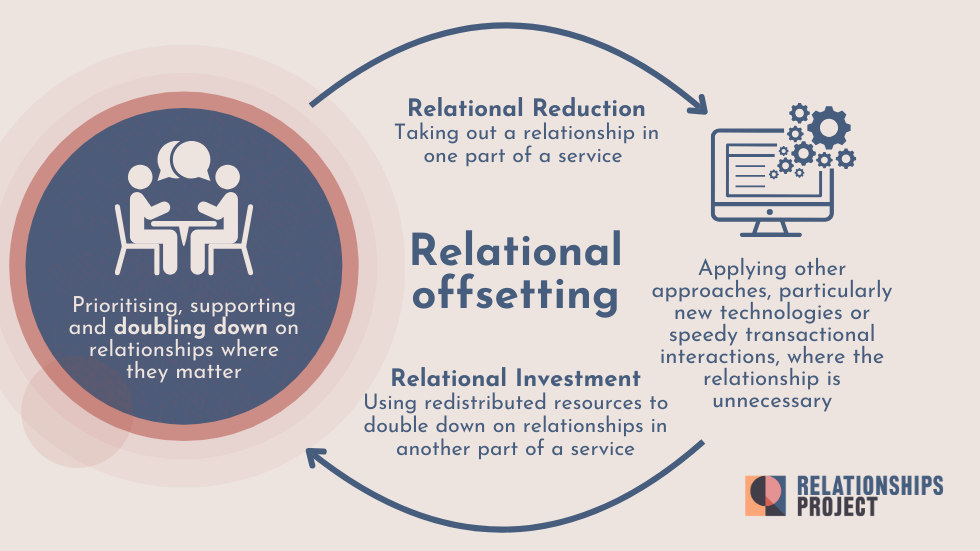

What is relational offsetting?

At the Relationships Project, we define relational offsetting as:

Taking out a relationship in one part of a service and using the resources to double down on relationships in another.

It is a way of prioritising and supporting relationships where they matter and applying other approaches – particularly new technologies, or speedy transactional interactions – where the relationship is unnecessary.

Crucially, relational offseting can help us to improve services without increasing the overall resource required.

Does it really work?

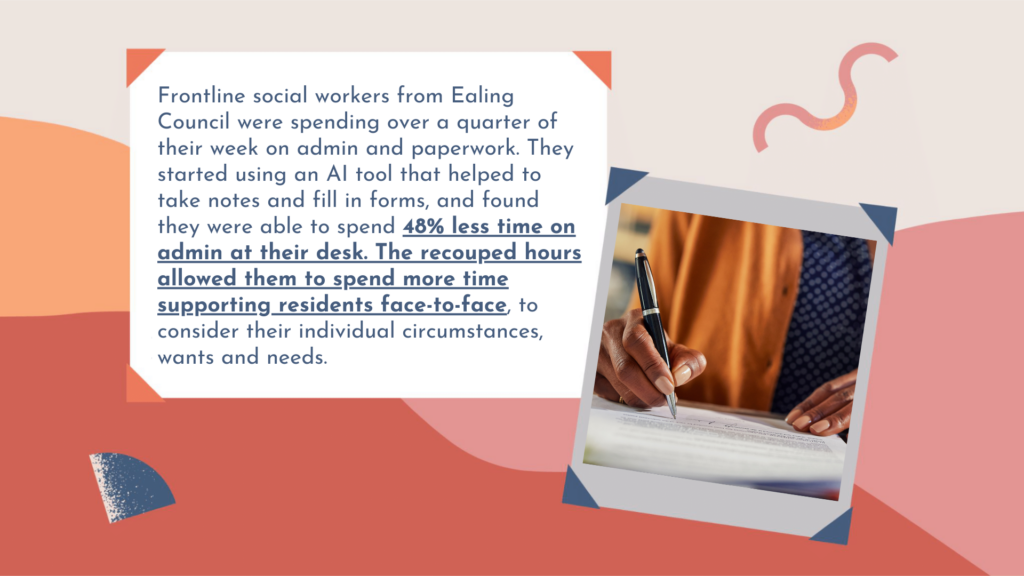

Frontline social workers from Ealing Council were spending over a quarter of their week on admin and paperwork. They started using an AI tool that helped to take notes and fill in forms, and found they were able to spend 48% less time on admin at their desk. The recouped hours allowed them to spend more time supporting residents face-to-face, to consider their individual circumstances, wants and needs.

Consistency is not key

Too often, our services and systems are set up to treat us all as homogeneous beings. Fear of complaints and accusations of discrimination drives a dogged consistency. But good outcomes across the board do not come from us providing identical services for everyone.

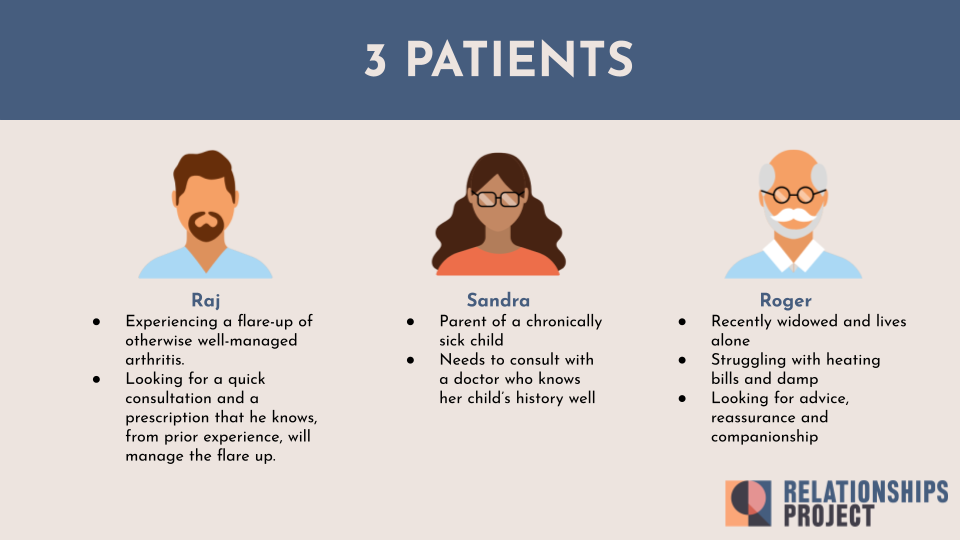

Three patients: an exercise

To help us think through how relational offsetting could improve services, let’s imagine three patients trying to book an appointment at a health centre.

First, there’s Raj. Raj is experiencing a flare-up of otherwise well-managed arthritis. He works full-time and is looking for a quick consultation and a prescription that he knows, from prior experience, will manage the flare up.

Second, there’s Sandra. Sandra is the parent of the chronically sick child, in and out of the practice regularly as different symptoms and complications arise. Sandra needs to consult with a doctor who knows her child’s history, and with whom she can co-create a plan of action.

And thirdly, there’s Roger. Roger is recently widowed and his children live in a different town. He is struggling with his heating bills, living in two damp rooms and increasingly suffering with respiratory conditions. He is looking for practical advice, reassurance and some support.

The health centre’s current policies dictate that Raj, Sandra and Roger are all offered a seven minute consultation with whichever GP has availability.

How might relational offsetting be helpful here? Three sets of questions are useful to ask:

Set one:

Where is a human relationship meaningful and necessary? Where is it material to the outcome?

Who is best placed to make and sustain the most effective relationship?

Set two:

Where is an efficient transaction an adequate or more satisfactory approach? Where are other machine enabled solutions preferable alternatives or helpful compliments to relational practice

What must we introduce to fulfil this function?

Set three:

How must we combine our various resources to double down on the relationships identified in set one? What is the right recipe, the balance of ingredients, for this service?

Raj doesn’t necessarily need to see the same doctor as he’s seen before, providing his case file enables the doctor present to understand Raj’s condition efficiently and without the need for Raj to repeat himself. He needs a prescription for the medication that he knows will work. This might not require the full seven minute slot that he’s been allocated.

Could machine-enabled solutions offer preferable alternatives or helpful compliments to the care provided to Raj by the GP?

Sandra and her child need a consistent relationship with the same doctor at each of their frequent visits. They might well need more than seven minutes, and they need the trust, understanding and collaboration that comes from that consistent relationship. For patients in circumstances similar to Sandra’s, researchers have found “a wall of evidence” supporting a one doctor relationship and continuity of care. The relationship is material to the outcome.

Could time freed up from Raj’s appointment be used to double down on a relational approach for Sandra and her child?

Roger, on this occasion, doesn’t necessarily need to speak to a doctor, but he does need to talk to someone. His problem does have significant implications for his health but it isn’t, first and foremost, a medical problem. According to NHS England, about one in five GP appointments goes to people who simply want someone to talk to – or who need advice about something non-medical. Roger could have a chat with Maureen, the receptionist. Her time is not as expensive as the GPs but it still has a cost and is necessarily limited to a warm but brief exchange. She could deflect the demand; she cannot meet the need.

Could Maureen’s health centre act as a connector and facilitator, setting up a daily coffee morning and supporting Roger to build meaningful and enduring relationships that can provide him with the support and companionship he seeks? It would need a skilled facilitator: we’re not talking about anyone with a big heart and a kettle. Both the big heart and the kettle are essential, but it would take more than that: relationship-centred practice is a craft. Connections made at the coffee morning would be more likely to lead to real reciprocal friendships than the encounter with the GP or even with Maureen. Precious time with medical professionals would be released for patients that need it most, and results would improve because we know that the quality of our relationships has a significant impact on our mental and physical health.

Why now?

We think that the extent of demand, the levels of need, the availability of money and the urgency of the political imperative will propel relational offset to the top of the public policy agenda in 2025.

1) The demand: we want it all

Over the last seven years, the Relationships Project has heard the same laments again and again: – “You never speak to a real human being”… “the service is too big, too impersonal”… “I never see the same person twice”… “I didn’t become a teacher/ nurse / social worker etc to do what I’m doing now”. At the same time, of course, most of us also enjoy the convenience of online services. We value the internet-enabled opportunities to learn from people with shared experience and we benefit from extraordinary advances in the availability of knowledge, the science of care and much else.

In truth, and as we noted in this recent blog about the modern hospital, “There are no easy binaries… We want the awesome science, all the shiny machines and death-defying medicine. We also want warmth and love and kindness. We want to have it all.”

2) The needs: public services are broken or breaking

We might argue over the causes but it is widely acknowledged that public services in the UK in 2025 are stretched to breaking point. From prisons to schools, hospitals to primary care, mental health services, to special needs provision, the stories are the same. Keir Starmer’s government was elected last year on a mandate to repair and restore, but the economy is struggling. If it can’t do more, it must do better.

3) The money: there is no new money but there will be current funds available for redeployment

We work a lot with managers and front line staff who we describe as “sympathetic but stuck”. They want to put relationships first but find it very difficult to break away from the constantly turning hamster wheel of day to day delivery. Technology can unstick even when, in and of itself, it isn’t the solution.

The Tony Blair Institute says that the UK government could save “up to £40 billion each year with the technology as it exists now. Over time, this technology will accelerate dramatically in its capability, and so will the savings.”

With a determined commitment to relational offset, an ambitious and progressive government could use some of this “technology premium” to double down on building and sustaining relationships where they really matter whilst still reaping significant savings where a personal interaction is unnecessary.

4) The political imperative: a window is ajar

On December 10th, Chief Secretary to the Treasury Darren Jones set out the parameters for the next Spending Review in a letter sent to all government ministers. The Review will determine the limits, and the priorities for all public spending from 2026 to 2029. The Treasury, he said, is looking for 5% savings. Some will be derived from “reducing waste”, some from “changing how services are delivered.”

Commenting further on the process, Rachel Reeves added, “By totally rewiring how the Government spends money we will be able to deliver our plan for change and focus on what matters for working people… By reforming our public services, we will ensure they are up to scratch for modern day demands, saving money and delivering better services for people across the country”.

We get a clue about what that rewiring might entail by referring back to the Chancellor’s summer statement: “we will embed an approach to government that is mission led, reform driven… and that is enabled by new technology including (utilising) the opportunities of artificial intelligence.”

To meet these Treasury demands in the months ahead, ministers must expand their understanding of what 21st century machines can enable the public sector to achieve. The full potential lies in understanding the technology as not only an end in itself, but also as the key to unlocking resources for building and sustaining the meaningful in-person relationships which are, for many people in difficult circumstances or trying times, the real agents of change.

This goes beyond what the Chancellor said, and may not be what the Chief Secretary had in mind, but it’s hard to see how government can “deliver a plan for change”, “focus on what matters for working people”, “save money” and “deliver better public services” without a determined commitment to relational offset in 2025.

Feedback and reflections

On 24th February 2025, a group gathered together on Zoom to explore these ideas further and offer feedback. Here are some of the key points that surfaced during the conversation:

We’d love your help in developing these ideas further. Please share any thoughts, questions or builds in the comments, or message david@relationshipsproject.org.

More from the blog

The Relational Neighbourhood

In brief Nick Sinclair and David Robinson have been mulling over a new blog for a while. It has been almost five years since their pandemic reflection on “the art of the covenant” (2020). A lot has changed since then but the underpinning principles of their thinking...

Letting the nation in: how a drive to promote relational practice could boost mission-based government

Introduction Nine months have passed since the general election. A new PM and a new generation of ministers have settled into post. They have had time to assess the legacy from the last administration and familiarise themselves with the ongoing work of every...

A relational approach to public policy: why it’s now essential

Introduction Nine months have passed since the general election. A new PM and a new generation of ministers have settled into post. They have had time to assess the legacy from the last administration and familiarise themselves with the ongoing work of every...

What a great articulation of a simple and potentially powerful idea! Looking forward to exploring this idea, and how it might be put into practice.

I wonder what your strategy is for getting the phrase on the radar of people making decisions about allocating public resources? Happy to discuss.