In brief

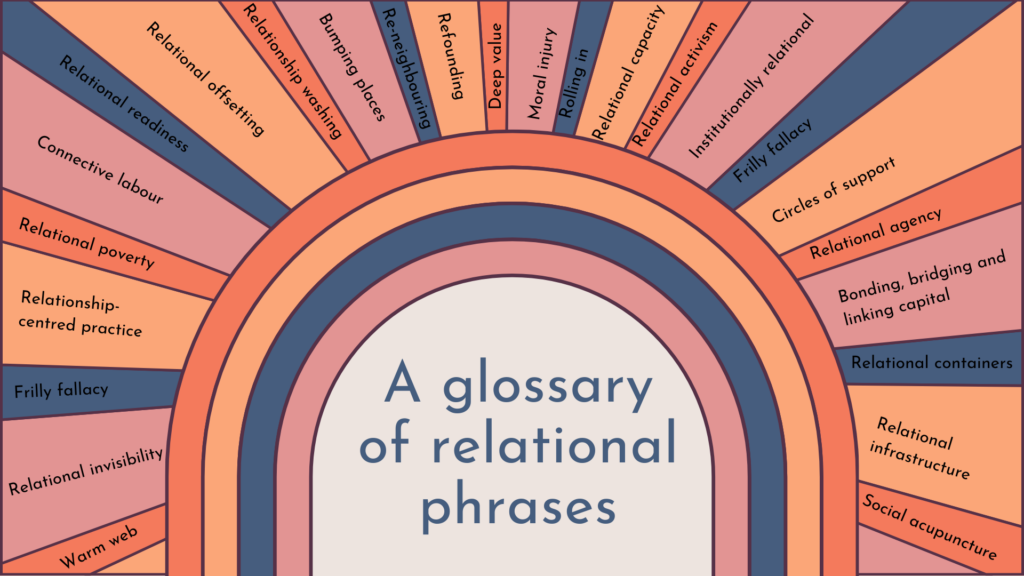

This week, twenty of us gathered on Zoom to discuss the language we use when talking about relationships. The conversation was inspired by the publication of a glossary of relational phrases and, while we discussed definitions on the call, the conversation carried us to many other fascinating places: from rituals in classrooms, to how neurodiversity relates to moral injury, to the difference between a red rule and a blue rule.

This note is:

- A memo to self (some of the things we want to carry on chewing over)

- An invitation to you, if you were not there, to think about this stuff with us

- A thank you to everyone who joined us, for the depth and openness they brought to the conversation. Below are just some of our takeaways. You’ll have more, and we’d love to read them in the comments below.

By the end of our conversation, Sharon told the group she felt “like a fruit cake being soaked in brandy.” What did she mean? Read on to find out.

Some things we talked about

Rosa Friend

We need more words

It is absurd that we talk about “our relationship” with our parents, our children and our friends, the children’s teacher, the doctor and the bank, animals, history, and food using the same word. Perhaps it’s a measure of our interest that we have more words for rain – downpour, spitting, cats and dogs, drizzle, mizzle and wetter than an otter’s pocket – than we do for relationships. We need to be familiar, and comfortable, with a wider vocabulary. Please contribute to this emerging glossary.

Recognising our different starting points

We shouldn’t assume a term we’re using means the same thing to someone else. If we assume another person thinks the same as us, and understands the world as we do, we miss the opportunity to learn from them. Instead of drawing boundaries around our definitions, we should be curious about our differing starting points.

The power of words

Naming an idea or an action can be powerful: a tool to advocate for change. And there is something important in being able to describe something to people who haven’t seen it yet.

After our Zoom conversation, we reflected on the story of Raphael Lemkin. In the early years of the twentieth century, he noticed that the mass murder of a group because of a group’s identity had no name; the Turkish massacre of Armenians and the Assyrians murdered in Iraq, for example, were unpunished crimes that allowed Hitler to believe his “Final Solution” could be achieved without international intervention. Painstakingly, over many years, and with lots of set backs, Lemkin coined the phrase, developed a legal definition and campaigned for the recognition of “genocide”. He devoted his life to changing the world with a word.

Relationality across cultures

We need to learn from other cultures where the breadth and richness of language both describes relationality with far greater subtlety and nuance and also creates the space for recognising and nurturing deeper practice.

Lana Jelenjev joined us to discuss her excellent article about relationality across cultures, and shared how the Filipino language has more words to describe the nuances of relationships than the English language, and how deeply embedded relationality is in the Filipino culture.

Relational death

A misreading of the term ‘relational depth’ as ‘relational death’ led to a great discussion about relational endings. We tend to think more about how we initiate relationships than we do about how we end them well. In the Case Maker, we tell the story of Switchback’s work with men who are leaving prison; many of whom have no experience of relationships ending well. Switchback intentionally supports men to experience relationships that come to positive, careful conclusions. Their work reminds us that we need to planning for relational endings, carefully, intentionally, and positively.

Facing moral injury and finding fellow travellers

We discussed how difficult it can be when there’s a disconnect between our values, and the conditions and systems we’re working within and what they allow us to do. If people you’re working alongside don’t share your convictions, finding people that do – even if they’re not within your organisation – can help nourish the soul and recharge the batteries.

Show how change has been possible before

Across the UK, and across the world, there are bright spots, where relationships are being prioritised and placed at the heart of things. The work of the people on the call was a reminder of this. To make meaningful progress towards large-scale change, one thing we need to do is to keep telling the story of where things are working – to help more people to see and be inspired by those bright spots.

A comment on the conversation

David Robinson

I had lunch in the same Canning town café a couple of times a week for several years. Whenever I went between 12.30 and 2.00, one table would be occupied by 4 men. They were probably in their late 70s, maybe older. They would arrive and leave separately, study a menu that they must have known better than the chef, order carefully and talk football. Occasionally the conversation would wander into politics or something on TV, usually at the instigation of the man with the walking frame who always read the Mirror whilst also eating and arguing.

One day I arrived after 2.00. Only one man was left and the paper was folded on the table. I said “has your friend finished with the paper?”

The man looked puzzled, “my friend?”

“The man who reads the paper”

“Oh they’re not my friends. They’re just the blokes I have my dinner with.”

I was remembering this today when we hosted a fascinating discussion about language and how our vocabulary reflects and influences our relational behaviour and ultimately shapes public policy.

Just as the “volunteers” on the allotment in this blog a couple of weeks ago thought of themselves as only “doing what anyone would do”, the “blokes I have dinner with” are also part of the warm web of relationships that keep us happy and healthy.

In a world with so much to worry about it may seem particularly small minded and self indulgent to bother about labels. Of course I’m not interested in changing how we talk, but I am interested in how we listen and in expanding the vocabulary that we use and understand.

Public policy frequently recognises the value of volunteers, checked, accredited and trained, but seldom sees the far larger numbers doing what anyone would do. Planners learn about the need for leisure centres and social clubs but ignore the bumping places – the school gates, the bus shelter, the café table with the blokes we have our dinner with.

We need bigger ears. We, and policy makers in particular, need to listen hard.

In the real world there is more nuance in the actual words that we use than there is in the policy makers dictionary. Inflexible and limited vocabulary begets inflexible and limited policy. Open and reflective phraseology begets inclusive and ambitious practice.

So, why did Sharon feel “like a fruit cake being soaked in brandy” at the end of the call? Because there were so many “deep and thought-provoking concepts” to absorb. A big thank you to everyone who soaked and absorbed with us.

Useful links

Throughout the course of the conversation, many useful links were shared:

- The slides from the session

- Glossary of relational phrases

- Lana’s blog on relationality across cultures

- A piece on the different levels of interaction

- The 3 Ps framework

- The Relationships Case Maker

- Colin’s article on Creating conducive conditions for relational practice to flourish

- Thinking about moral injury, work and neurodiversity

- Starting point on regeneration: https://www.thrivableworld.com (This is from the work of Michelle Holliday on “The Art of Thrivability”)

- Can a ‘structural competency’ approach improve the safeguarding of diverse marginalised communities from exploitation?

- Useful examples of the shift toward relational and inclusive approaches in whole-place approaches to adopting trauma-informed places that go toward preventing social harms:

- A blog we wrote about permissions which feels relevant to the idea of red and blue rules

- Example of introducing art practices and tools and impact this has on the relationship between social care practitioners and young people.

- An example of a good ending

- Triple wellbeing

- Interesting on relational depth

- The book Listen by Kathryn Mannix

- This research blog by Sharon Court, written during a six month internship with ARC Wessex, looking at whether social pedagogy might be a good fit for PPIE in healthcare research

Further reading

How to have it all: relational offsetting

In brief This month, the UK government announced a huge public rollout of AI. If the plans embrace relational offsetting, it could allow us to prioritise human relationships where they really matter. Our hope is that 2025 will be the year when relational offsetting...

A glossary of relational phrases

In brief Over the last few years, many of us have been talking more and more about the importance of putting relationships first in our organisations, systems and communities. In being party to some of these brilliant conversations, and developing our own thinking,...

What we mean by relationship-centred practice

Key Concepts | What we mean by relationship-centred practiceRelationship-Centred Practice puts relationships first. It unlocks potential and meets need by positioning meaningful and effective relationships as the first order goal, both an end in itself and the means...