Dr Nick Barnes

In this extraordinary contribution to the Joining the Dots series Dr Nick Barnes looks ahead to a post-Covid future, arguing that to build a better society, we must address inequality and redress power structures.

Nick works as a Specialty Doctor in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, as a Cognitive Analytic Therapist and Honorary Senior Lecturer at University College London

This is an extended contribution to the Joining the Dots series. We encourage you to read it in full as it is full of fantastic insights but, if you’d prefer, an abridged version can be found here.

Relational thinking, not only supporting the frontline

The recent outbreak of Coronavirus within the UK produced unparalleled planning and action within the NHS and other frontline services, demonstrating the considerable adaptability of the workforce across a whole array of sectors. Medical and nursing staff have been trained in days to be redeployed to working on the frontline, new hospitals have been built and staffed in conference centres, whilst primary and community services have transferred onto online platforms within a matter of hours.

From a service which has been repeatedly lambasted for being slow to change, the NHS and its workforce, supported by wider communities and networks, have been remarkable in what they have achieved in the last few weeks.

Alongside the acute medical need, there has been a flurry of activity in enabling staff to get adequate emotional support, psychological PPE, with psychologists, psychiatrists and mental health workers offering support to their colleagues on the frontline, whilst also thinking about the fears and worries of those with more enduring mental health needs in the community and in confined settings. Through Social media and Apps, professionals have been able to offer advice and opportunities for dialogue about self-help, mindfulness or stress management, helping people think about what will help them cope with the “COVID-anxiety”, whilst offering caution about not intervening too soon or too early with any proposed psychological approaches to trauma or distress. The focus has mostly been on ensuring people know “its ok not to be ok” – being anxious is a perfectly healthy response to an abnormal situation.

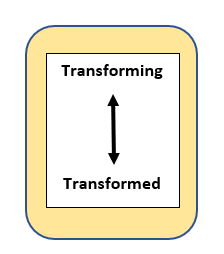

But as we start to consider the ending of the lockdown(s), it is perhaps some of the broader thinking from psychologies and psychotherapies, through more developmental and relationally-informed models, that might offer some useful learning and expertise.After all, therapy is all about enabling the possibility of change, and the COVID-19 pandemic is very likely to be an event that initiates that possibility. However, if we are to ensure that this is “Change for the Better” [1], then we need to think carefully about how we enable exits from this lockdown.

We’re all in this together

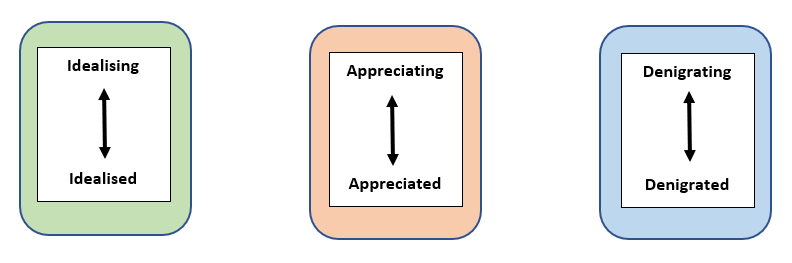

If there is one thing that has become increasingly clear over the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is the extent and severity of inequalities that exist within our society, and our reluctance to being willing to name and address this systemic injustice. Whilst much of the reporting surrounding the lockdown has been directed on those selfish enough to “break the rules”, there has been little discussion regarding the privileges of having a private garden, or access to home deliveries of shopping, both of which are clear markers that differentiate between the “have” and “have nots” in these current times.And yet, as we start to see the emerging predictions about the economic cost of Coronavirus and the subsequent downtown turn in production and employment, we run the risk of reinforcing the polarity of this inequality, unless we use this moment of crisis as a time to re-think and re-connect with ourselves and our priorities for the future.Within the space of weeks, the NHS was transformed from being a dinosaur and obstruction to the inevitabilities of free market determinism into being the embodiment of heroic endeavour – with doctors, nurses and all other front line workers being rightly recognised for their incredible bravery and courage, in the face of the uncertainties and risks unleashed by the emerging global threat. The nation stopped and clapped its gratitude and thousands of volunteers came forwards, as the NHS shifted from a position of being dismissed and denigrated, to one of being appreciated and valued – and possibly even idealised. Whilst the threat exists, and we strive to “flatten the curve”, politicians and the wider public will continue to recognise and value the dependence on our frontline heroes, and hence the NHS will continue to hold this idealised pole. But as we start to come down the curve, and start to explore our exits, then the realities of exhaustion and isolation fatigue might start to kick in, and the discomforts of the post-COVID world may become increasingly apparent.

With the NHS oscillating between a polarised position of idealisation and denigration, it, in many ways, reflects the dangers within society as whole, as well as within us as individuals.

The last 40 years has seen a massive reinforcement of inequalities within our society, and the NHS has often been the metaphoric football which gets kicked about, either to be blamed for failing to address the needs of people in this increasingly divided society, or being placed on a pedestal of expectations of the wider public, only to reinforce the sense of disappointment and subsequent anger.But when we think about an individual who may finding themselves swinging between extreme positions of feeling perfectly cared for, through to experiencing a sense of being dismissed and disregarded, then are often drawn to be thinking about what traumas or difficulties may have occurred that allow for these patterns of reactions and responses to have become so entrenched.

Chronic neglect

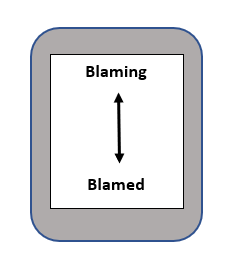

Alongside the rising inequalities that have been so strongly endorsed and reinforced over the last few decades has been the systematic underfunding and undervaluing of the NHS and Social Care, which has further entrenched the inequities evident within our society; inequity that we have been so keen to ignore or attribute blame to others, but the cost of which is now becoming so acutely evident. The absence of PPE for frontline staff in hospital and community settings is such a stark example of this inability to think about the protection of the workforce, and subsequently those that they serve, the wider public, with staff being encouraged not to be “wasteful”, rather than any admission of accountability or responsibility from government ministers. Further when asked if there may be an apology owed for putting staff lives at risk, the response was to sympathise with frontline workers perception (feeling) of threat, rather than to take ownership and offer a formal apology. “Sorry is the hardest word”, and it certainly seemed to be the case for this current government, but by failing to take responsibility, there is then a considerable loss of trust in what is being said, and with a loss of trust, comes a disengagement and a reluctance to comply. But if there is a failure to comply, then those that “break the rules” of the lockdown can be blamed for the risks being posed to the NHS staff – the responsibility has been shifted onto the #COVIDIOTS, for whom we can unleash an army of Twitter abuse, and ministers can feel satisfied that they are striving to do their best, even if others remain ungrateful.

The NHS will last for as long as there are folk with the faith left to fight for it

War time spirit and building on the nation’s resilience

There has been a desire, for some, to draw analogies with the War-time spirit, facing the common enemy within this crisis, and it is possible that a “Keep Calm and Stay at Home” approach may be a useful way of reinforcing a unifying message – especially if delivered from a Prime Minister who models himself on the wartime lead. But even our self-styled Churchillian, by failing to observe the most basic advice from the World Health Organisation, nearly paid a fatal price – and we can but dream that his gratitude to the staff of St Thomas’s Hospital may reflect a broader shift in his overall outlook. But there has been a wider discussion about how this crisis will demonstrate the resilience of the Great British public. In the face of adversity, Britain will once again “rule the waves”, or at least dig in and think of Dunkirk, and an undercurrent of nationalistic reserve may have contributed to our lack of willingness to take notice of the warnings coming from our “European colleagues”. But we need to be cautious about what we mean by resilience, if we are to think about how we will “overcome this adversity”.If we continue to allow for a definition of resilience that marries a neo-liberalist pursuit with a focus entirely on the individual then we will simply ensure that overcoming the virus will then reinforce the current status quo, exaggerate the current inequalities, and allow for a post-COVID world of great disparity and conflict.This definition of resilience that focuses on “grit” and the need to develop character, reinforces the individual’s sense of disconnect and alienation and subsequently we emerge from this crisis none the wiser, and potentially at even greater risk. But if we consider resilience to be about “beating the odds whilst also changing the odds” [2], then this allows for us to all have a sense of agency and belonging in how we might “be the change” rather than be subjected to changed. The post-COVID world is going to be a profoundly different one to the world we left behind in 2019. The economic impact alone poses an enormous threat to jobs, to productivity and to lifestyles, all of which will then impact upon health, social care and the need for welfare and support.

If our focus remains on the individual, then we will simply reinforce the polarisation within our society. But if we allow ourselves the time to acknowledge that we need to be more focused on our communities, and on the relationships, we have within our communities, then the Coronavirus pandemic offers us a genuine opportunity for change and a more sustainable future.Just prior to the arrival of COVID-19 upon the UK shores, Greta Thunberg addressed thousands of young people on College Green in Bristol, noting the anxieties and worries so many have about the threat of climate change to the survival of our planet. Her articulation of such an existential threat generated mixed responses, and yet COVID-19 has demonstrated so clearly our vulnerability. The need for lockdowns across the world has even given people the time to take notice of the changes going on around them – with recognition of Bird Song being a common feature on Twitter and Facebook. The loss of travel and shutting down of industry has allowed us to experience the immediate impact of reduced pollution. The argument is clearly not to suggest that we need a global pandemic to enable us to address climate change – but rather it is that COVID-19 has perhaps given us a window through which we can consider taking notice of the world around us, and once again, exploring the possibility of change.

But if we are to enable meaningful and sustainable change, then we need relationships, trust and agency. We need to think about ourselves in relation to others, as well as in regard to what is going on within ourselves, and we need to believe that we can trust in those around us to support us.We went into this crisis on the back of one of the most divisive and polarising debates within the UK, with Brexit offering no sense of resolution of inequalities and alienation that drove much of the desire for “independence from the EU”. Britain became a country that others looked in upon, completely unrecognisable from the “Green and Pleasant Land” so notoriously projected across the world in costume dramas of yester-year.

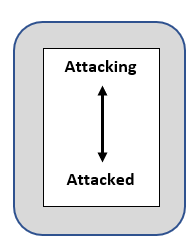

But Brexit embodied the divisions and inequity of UK society and enabled a culture of threat, intimidation and menace to be mainstreamed, with even the murder of an MP failing to allow for a window of reflection – reinforcing a permission for violence.

This pandemic has not been a great leveller – disease does not affect all equally – but rather, COVID-19 demonstrates and reinforces the firmly established and entrenched inequalities. Even within the first week of the lockdown there was a reported 25% rise in reports of domestic violence, with no clear contingency plans in place for how women and children might be able to find a safe exit under the newly imposed restrictions. By week 4, the homicide rate linked with domestic abuse had been estimated to have doubled. And living within a home with a constant threat of domestic is laying the foundations for significant emotional and mental health needs of children and young people for years to come.

Those living within care homes across the country didn’t even count as part of the official statistics for deaths from COVID-19. The staff in these settings had not access to testing or proper PPE, with the elderly being given a very clear message that their loss is less important.

For others, this pandemic has been an opportunity for profit, with the current leader of the House of Commons having a 15% stake hold in a capital management company that speaks to Coronavirus being a “once in a generation” chance to cash in on investments.

The distinction between a humane society and an inhumane one is that a humane society sees human need as generating reason to help, and an inhumane society sees human need as an opportunity to profit

But a quick overview of the figures for those that have died in the UK and US shows a profound overrepresentation of men from BAME backgrounds. Looking at staff who have given their lives on the frontline for the NHS, then they are even more disproportionately from BAME and migrant backgrounds. The NHS is entirely dependent upon the very staff that we were so quick to dismiss and reject in our desire to Get Brexit Done, and this paradox has been so beautifully articulated in the “You Clap for Me Now” poem and video circulating in week 4 of the lockdown. Perhaps, whilst we have the space to show our value and appreciation for the NHS, we might also find the room to consider the impact of our previous decisions on their lives and their overall sense of safety and threat.

Seeking Exits

Hence if we are to start to talk about an exit strategy – not only on how we might exit the lockdown, but also move forwards in a post-COVID-19 world – then we need to be thinking about how we can understand and address these inequalities, and seek to have a more relationally based society. It is not going to be enough to “just get back to normal” as “normal” is very unlikely to exist, and “normal” was part of the problem in the first place. Business as usual, or “normal” was what had allowed Thatcher to claim, “there’s no such thing as society”, and we have been living within the shadow of that quote for the last 40 years.

There has been a lot of guidance on social media about how to look after ourselves and how we need to remain connected, but as we start to break the lockdown, we need to be thinking about how we can start to embrace a culture that is about connecting and feeling connected – embracing a paradigm that places relationships at the heart of what we do.

If we remain stuck in repeating bouncing between a place of either idealising or denigrating, of idolising or dismissing – be this about the NHS or about any other representation of our society – then we will simply reinforce the inequalities that exist, and drive the sense of alienation and distress that is experienced by so many, and was so forcefully demonstrated through Brexit. With the loss of employment and the rise in poverty, people are going to feel even more alienated from a society that embraces and idolises the few and disregards the majority.

Inclusion and Expertise

We therefore need to use this time to explore the change that could be possible – but also to acknowledge who needs to be involved in that change. For too long, times of change have predominantly been imposed from above, with the expert being seen in a position of authority and power. Expertise has been located within the domain of privilege and has not sort to understand or learn from those with differing expertise and experience. The press briefings from No 10 during this crisis have been a classical demonstration of this lack of understanding, with NHS and PHE leaders being quite surprised that establishment views are being so undermined and challenged, without any appreciation of the experiences of others. Blaming people for going out into a park and putting the public in danger feels quite an easy target, and yet there was a clear failure to offer any alternative suggestions for how those living in crowded tower blocks and estates. The guidance from ministers and scientific leaders resembled the response of the May government to the Grenfell Tower fire, seeking to find easy targets to blame, rather than to respond with compassion and empathy. Observing from a distance, it seemed as though the NHS and PHE leaders had forgotten they were allowed to have a view and opinion that might be different to that of the government – after all, they are there as the leaders of the workforce that were being sent into the front line without adequate resources. If we are going to think about a war metaphor, then rather than focusing on the Spirit of the Blitz, perhaps recalling “Over the Top Lads” may be a better analogy.Change requires relationships, trust and agency

As noted before, if we are to bring about change, and if we are to learn from this experience, as well as find a way of minimising the threats and dangers that will emerge in the post COVID world, then we need to ensure that we are thinking about our society being focused and based on relationships and less directed by the individual.

But to do this we also need to be able to trust in others. If we have been traumatised, abused or neglected, then building that trust can take time, and requires a consistent other that will allow us to feel connected.

Our post COVID 19 world needs to reflect on what we may have learnt in our hyper-localised enactments of lockdown, and how we might build on these experiences and share our expertise. It is those that have been building the bridges in communities, delivering food parcels, or checking in on neighbours, who are now better placed experts than many of our politicians.Likewise, those parents who have lived the nightmare of knowing that their children have been running county lines prior to the lockdown may recently have had an experience of inclusion and connection within their families that might feel new and unique, and certainly needs thinking about and exploring if we are to see the post-COVID world having an impact on experiences of exclusion and exposure to knife crime and violence.

Exits informed by Inclusion, Connection and Coproduction

But accessing and hearing these voices, learning from and building on people’s experiences, and then finding settings and contexts in which people can share their experience, is primarily about enabling agency.In a post COVID world, people from all walks of life need to believe they have some sense of control and agency in their lives.It could be argued that a pandemic represents a time when people feel completely out of control, but this has not been the plague of the 14th Century, this has been a televised pandemic and we have all been able to see whether we can have control or not, by how our governments have chosen to act or not. The current perception seems to suggest that the UK government took its time to consider what action to take and was even exploring a model of herd immunity to manage this outbreak. Sadly, for the government the herd did not welcome being part of an “obedient flock”, and this must be an important lesson from the current crisis.

Hence building on what we have learnt in our COVID-19 bubbles, then if we are to believe that this is a window of opportunity for change, and wish to ensure this is a change for the better, then we need to acknowledge where we have made mistakes, but also reflect on where we have been able to build relationships, connections, trust and subsequently agency.Greater democratisation, transparent accountability and opportunities for inclusion of all voices and experiences are just some of the ways in which people will feel that they have genuine agency and control in the Post-COVID world. For it will be through inclusive, connected and coproduced thinking and doing that people can begin to believe that change may be not only possible, but also sustainable.