In brief

Language matters. Words shape ideas and ideas shape action. We often use the words relationship-centred practice. In this blog David discusses his understanding of the phrase.

This is a discussion piece with a set of working definitions and assumptions. We want to start a conversation and would love to hear from you: What do you find helpful? What isn’t? And what’s missing?

We’ll be discussing the how, what and why of relationship-centred practice at a convening at Northumbria University on 23rd November and will share the thoughts and builds of participants.

What do we mean by relationships?

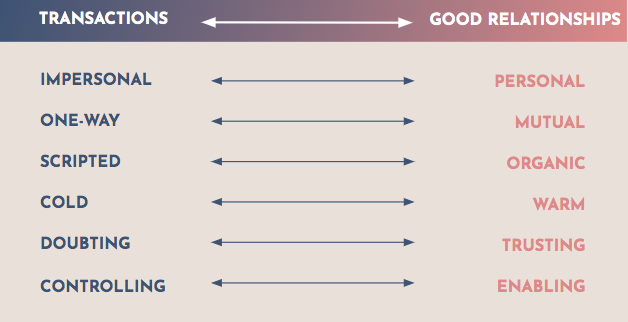

When we talk about relationships, we’re talking about good relationships; relationships where each party has the other’s interests in mind, where there is mutual benefit, trust and warmth. We recognise that relationships can harm one or both parties and these, of course, are not the sorts of relationships that we are advocating for.

We don’t think there can be one single definition of a good relationship but we do think that good relationships share some characteristics which set them apart from transactional relationships or bad relationships.

What sort of relationships are we talking about?

We’re interested in a wide range of relationships, from the relationship between a GP and her patients to the relationship between the patients who use the surgery; from the relationship between a teacher and his students to the relationship between parents of children at the school; from the relationship between neighbours to the relationship between communities who see themselves as being different to one another.

In many ways, we are agnostic about who the relationship is between, but we’re fascinated by the change that those relationships unlock.

Understanding relationships to be an agent of change is central to the concept of relationship-centred practice. We believe it is not only possible for one human being to make a real and lasting difference to another, it is often, in the most difficult circumstances, the only thing that does.

So what do we mean by relationship-centred practice?

Relationship-centred practice puts relationships first. It unlocks potential and meets need by positioning meaningful and effective relationships as the first order goal, both an end in itself and the means by which other goals will be achieved (like better health, stronger communities, greater job satisfaction) It is the principle on which we build successful services, a favourable and equitable economy, fair and effective government, flourishing business, safe, happy, healthy communities.

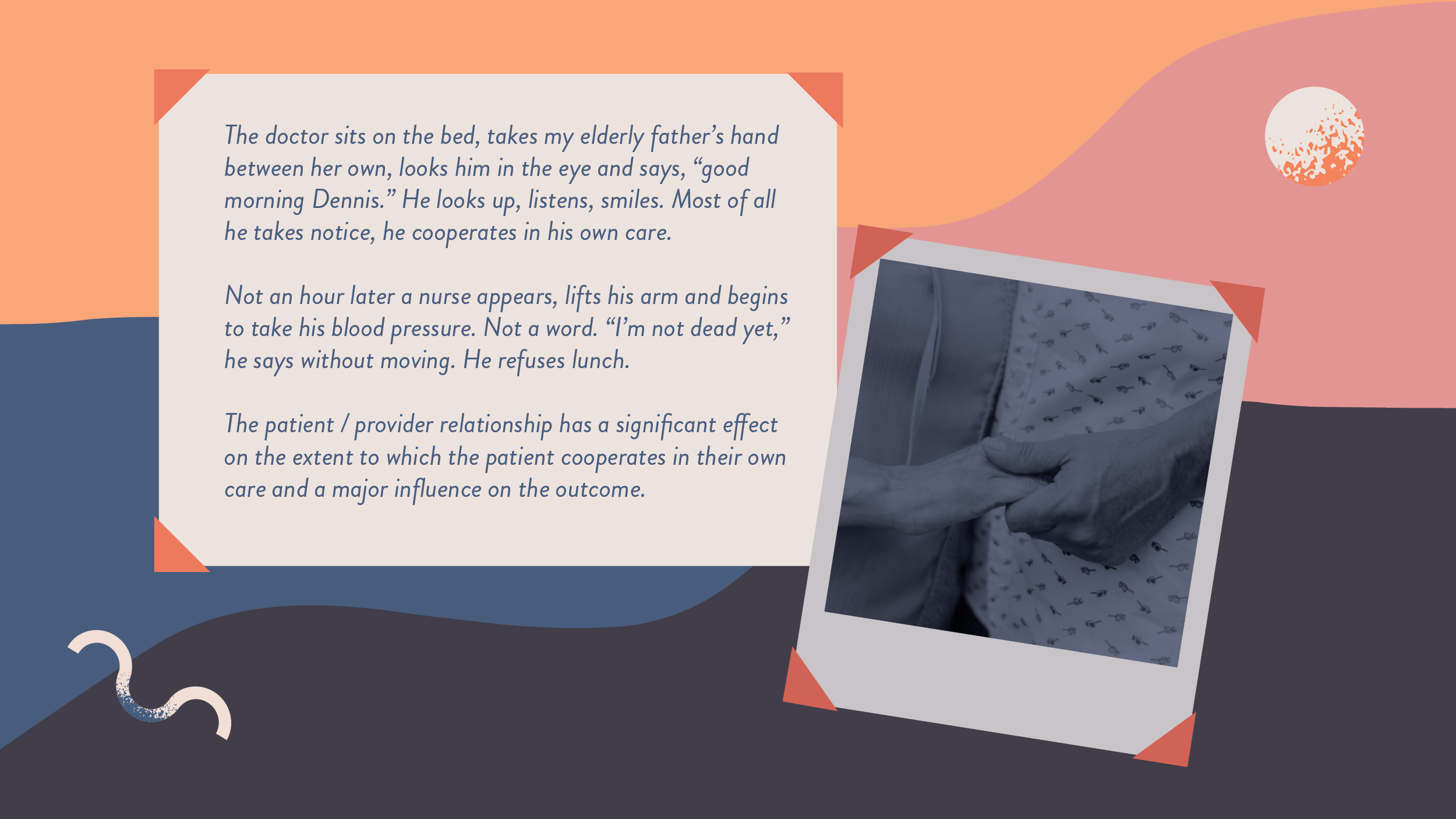

Relationships are everywhere in our organisations, in our rules and protocols and in our day to day lives. We all have stories to tell about the doctor we trusted, the teacher who listened, the relationships that nurture us and strengthen us and the ones that don’t. We know that everything works better when relationships work well because it is our universal experience and because there is extensive evidence. Relationship-centred practice builds out from this common sense of how people flourish, tackle adversity, build capability and fulfil potential.

How does it work?

A relationship centred approach is characterised by empathetic behaviours such as positive listening, active collaboration, a commitment to continuity, kindness and mutual trust. There is a shared sense of purpose and also of agency – “we can do this together”, capacity for challenge, for holding tensions alongside compassion and forgiveness, a focus on assets rather than deficits and sufficient versatility to adapt the practice to the individual rather than fit the individual to the programme. It is informed by experience, but not scripted. The most effective relational practice is not enforced from without. It is compelled from within, willing and dynamic.

Relationship-centred practice is about what we do and also about how we do it. Thus the urban planner focuses on how the built environment can best enable social connection. This is what they do. And they set up opportunities for residents to engage in imagining and co-creating the new landscape. This is how they do it. The combination is relationship-centred planning. (For more on this concept, take a look at the excellent HowNotWhat website).

Relationship-centred practice requires us to loosen the reins on a strict adherence to process and rigid expectations around predictable outcomes. Given every individual is unique, every relationship has a slightly different shape and takes a slightly different course. Relationality Lab explains:

In a jet engine relationships are designed to be static. Every part changes the part around it in ways that are predictable and repeatable. In a relational system like a social movement our goal is for new relationships to form, and for the parts of the system to change one another in new ways. These changes compound on one another, making prediction impossible. The more we are achieving our goal of building a relational movement, the faster our ability to predict drops away. We sometimes refer to this paradox as the curse of transactionality.

When is relationship-centred practice relevant and useful?

Activity that centres on building and sustaining strong relationships is helpful in multiple contexts.

As an end in itself

For the care worker or the school mentor, establishing and sustaining an effective relationship is fundamental to the purpose of the role. The relationship is a valuable and important outcome in and of itself

As a means to an end

For the teacher, behaviour, attendance or academic performance will be the ultimate purpose. Effective relationships are fundamental to the pursuit of these goals. Good relationships are the means by which these other goals are achieved

As a universal enabler

For the neighbourhood housing manager, the disaster planner or the local police, strong individual relationships aggregate into safe, strong and resilient communities. The nature of their approach will shape the environment into one where relationships flourish or flounder

It is also important to note that focusing on one of the above often achieves other things as well. Single discipline lines of academic enquiry incline us towards thinking about relationship-centred practice as a single purpose approach to education or health care or policing. This misses the vital point: strong communities with good relational networks are healthier and safer and more economically effective. People, organisations and societies that are better at relationships are better at everything.

People who are more socially connected to family, to friends, to community, are happier, they’re physically healthier, and they live longer than people who are less well connected.

What are some of the barriers to relationship-centred practice?

We talk about relationship-centred practice being common sense but not common practice. There are many reasons for this, some at a systemic level, others at a personal level, and many more somewhere in between. Here are just a handful of the things that can help or hinder relationship-centred practice:

The environment

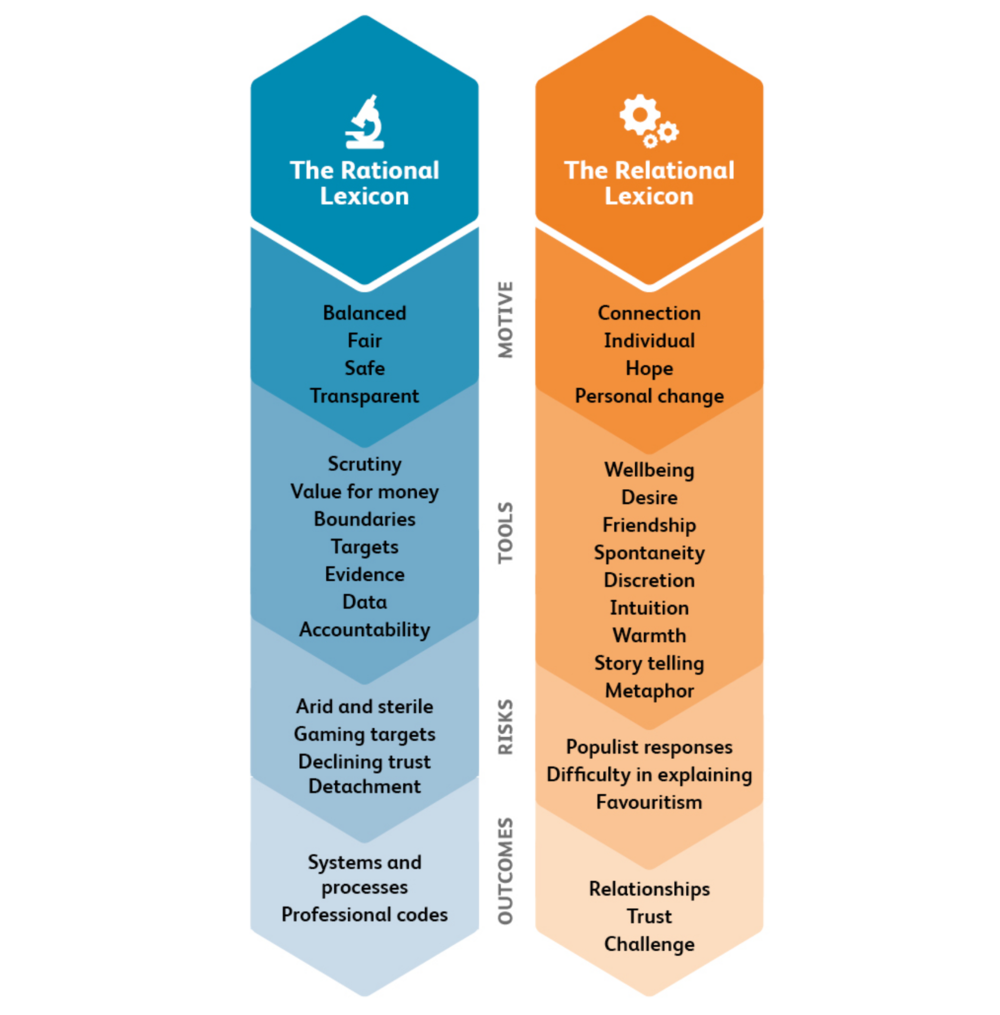

We often talk about creating the ‘conditions’ in which relationships can flourish. As Relationality Lab explains, “Some environments are better at generating and maintaining relationships than others. A community that trusts one another gathering to share a meal is more relational than, say, Twitter”. In Kindness, emotions and human relationships: The blind spot in public policy, Julia Unwin describes how digital technology and the rapidly growing ability to process complex data has stripped out personal interaction and enabled shifts in managerial models and protocols towards what she calls the “rational lexicon” – ‘the language of metrics, and value-added, of growth and resource allocation, of regulation and impact”. The dominance of the rational lexicon across so many of our services and organisations makes it very difficult for practitioners to centre relationships in their work. Value for money, targets, data and an emphasis on processes crowd out discretion, intuition, warmth, trust and relationships.

Source: Carnegie Trust

The evidence

Policy makers or service managers often tell us that relationships are important in their work but their top priority is improving health outcomes, or reducing anti-social behaviour or lifting departmental standards. We say that relationship centred practice isn’t an alternative to any of these goals, it’s the how, the route to achieving them. But the supporting evidence is insufficiently compelling because it is dispersed across many disciplines, terms are differently defined, measurement contested and practise learning fragmented and wasted. Making a better case requires more work, and more collaboration, on evidence and learning. To move the dial on practice we need to get better at making the case. This begins with developing the study of relationship-centred practice as an interdisciplinary space, understanding the commonalities, identifying the gaps and distilling the implications.

The craft

Whilst we all know good relationships when we feel them, building and sustaining good relationships is a craft that, like any other, can be taught and learnt and gets better with practice and yet is almost entirely ignored in our educational systems. We can’t rely on our instincts alone to build relationships in a world teeming with difference and diversity. We heard, in our conversations with 100s of relational practitioners, a shared desire to connect with one another, to learn from one another, to lean on one another in developing and applying relationship-centred practice. We hope to help meet this need over the coming years.

Why is all this especially important now?

Through The Relationships Observatory, we noted evidence of change during the pandemic with systems and structures, driven by necessity, becoming “more horizontal, less hierarchical, more can do, less defensive, kinder, more emotionally responsive, cemented by solidarity rather than compliance.” Our sense now is that most have begun to change back, not necessarily to the same extent or everywhere, but largely and in most places.

A renewed drive for more relational approaches is particularly important now, post Covid, in a cash strapped welfare state, and a struggling health service, that were designed to meet the needs of a different age.

Social care, for instance, wasn’t a priority for Beveridge when lives were shorter and care was largely provided within the family by women who were less likely to be working outside the home.

The NHS was built to tackle one off illnesses. Polio or pneumonia can be cured by an expert with a process, but chronic conditions today, like diabetes or obesity, require patients to be active agents of change. Needs have changed, and we understand them differently, but systems haven’t. Now, says Hilary Cottam, we need a “relational welfare state” that creates “capability rather than dependence”.

“Connecting human beings together” in a relationship centred approach to primary care in Fleetwood has shown what can be achieved. Here GP Mark Spencer says:

The last two years [there has been] something like a 20% reduction in A&E attendances and acute emergency admissions from people registered with a Fleetwood GP, whereas across the rest of the geographic area the activity is still going up by 3 or 4%

We won’t meet the challenges of the next year, let alone of the next generation, with an approach to our shared lives that is impersonal and centralised, defensive, distrusting, and fearful, transactional, codified and bureaucratic. These are the dominant behaviours of the society we have built. They are not the defaults that will enable us to thrive in the future.

Next generation public services are emerging now, often still fragile, experimental, and localised, but built on principles that are liberating and empowering, organic, responsive and personal.

Much of this work isn’t a “service” as Beveridge would have understood it. It is the considered practice of building and sustaining effective relationships, individually and collectively. Might it prefigure a future when relationships between people, rather than between service users and providers, citizens and the state, or customers and the market, is widely regarded as the organising principle; common sense and common practice?

I love what you are doing at the Relationships Project and the way that you are doing it. Honestly, it’s one of the most wonderful initiatives I’ve come across in the last few years, and the work that you are doing is making me bolder and more confident with putting relationships at the centre of my work.

As a small note of constructive challenge – and I really appreciate that you state that you value collaboration, kindness AND constructive challenge – the contrast that you draw between relationships that are Transactional and relationships that are Good doesn’t quite work for me, for two reasons.

First, because as you note for some engagements – e.g. buying a train ticket – a Transactional relationship will suffice and in effect be good (as it will deliver the result you want).

Second, because whereas Transactional provides a summary of the characteristics of those sorts of relationships, Good does not do that in quite the same way.

I know that this is something that you are mulling over. For me, I might use the word Compassionate (or Kind, or, in some circumstances, Loving) rather than good.

Another option that came to mind for the two poles was Mechanical and Organic.

Keep up the good, kind and loving work 🙂

alan