Days after the Prime Minister launched a bold new Civil Society Compact, the Health secretary announced a major public consultation on the future of the NHS and the Chancellor introduced a budget that squeezed frontline services in the short term, invested in the longer term and offered some sparkles in the small print. In this two-part blog series, we explore how a greater focus on relationships can – and must – guide the way ahead.

Here, in part one of the series, David Robinson argues that good relationships and effective relational practice must, now more than ever, head the policy agenda. In part two, Rosa Friend draws encouragement and practical examples from the work of local authorities and their communities in the dark days of lockdown.

Few people listening to the PM speak last week will have been thinking about digging onions, but I was.

Sir Kier was launching the new Civil Society Covenant – guidelines and aspirations for a new relationship between government and civil society from the biggest charities, through to individual citizens. He talked as he has done several times in recent months, about a “society of service”. It reminded me of a conversation I had with social workers some years ago. They told me about two elderly women. They lived independently and both caught the flu in February. The first stopped eating, forgot her regular medication and began a rapid decline. By Christmas she was living in a nursing home. The second had been a member of an allotment group. Other members brought her meals, they asked about her medicines and followed up with the doctor. Three months later she was back digging onions.

None of the allotment friends recognised themselves as a carer. Or as a volunteer. They were just, they said, “doing what anyone would do”.

“Anyone” may be an exaggeration but we do know that many people would. When needs were most widespread in the grim days of lockdown, 8.95m active neighbours were caring for one another or involved in some other form of community activity.

The challenges confronting government today are different from those of 2020 but no less acute. A mission-led government should not expect to solve them with the statecraft, or the singular, technocratic, highly centralised, top down and fundamentally unrelational instruments, of its predecessors. It should expect to utilise all of our talents and our greatest natural resource – human beings being human, working together for the common good.

Call it, if you will, a Society of Service. We call it common sense.

A Society of Service

The Covid neighbours were not, as ministers were wont to call them at the time, a “volunteer army”. They were willing citizens making a moral choice and a personal commitment. Although government can’t capture and corral this spirit of fraternity, it can nurture an ecology that enables relationships to thrive, or it can, as it so often does, squeeze them out with a drive to control, with bureaucracy, or with technology, or with aversion to risk. There are choices to be made.

A Society of Service would prioritise relationships. Everywhere and in everything. In lockdown, rules were relaxed, relationships did come first, staff and communities were trusted to know and to do the right thing. It worked then and it can do again.

The new government should switch the default, stop thinking and working from the top-down and start from the bottom-up, focusing on what government can do, coordinating, convening and representing, and giving others the resources and the authority to do what they do best, prioritising the involvement of citizens in the services they use and in the places where they live – a stronger combination of listening, empowering and relationship-centred practice. In part two of this blog series, Rosa suggests some of the practical, cost-neutral steps that both central and local government could take now to make that switch.

A Society of Service should also be about how government leads its own workforce as well as about what it enables us all to achieve together. Ministers should trust their own people – teachers, nurses, carers – to make the right decisions, to do the things that made them want to teach and nurse and care, unleashed from excessive regulation.

The best services are flexible and strengths-based and deeply rooted in meaningful relationships. We know that this will deliver better public services and also better value for money because we have the evidence and because public servants are not a separate species. “They” are “us”.

Better value for money

“Better value for money” looks even more important after the budget than it did before. Whilst the Chancellor’s “budget for growth” makes essential investments in public infrastructure, the modest increase in revenue spending will be more than eaten up by inflation, particularly wage increases, and the National Insurance hike. Public services could be salami-sliced, again. Or they could be re-founded on the principles of relational practice.

Here are a couple of lines in the budget statement small print may not have attracted the biggest headlines but might actually be the best news (and, full disclosure, not a million miles from the Service Transition Fund which we have been advocating for).

“The Budget also announces a new Public Sector Reform and Innovation Fund, to support the development of a new approach to improving public services. The Budget allocates £165 million of this to a range of projects in 2025-26, including to support foster carer recruitment and planning reform. In addition the Budget allocates £100 million of this over the next three years to deliver innovative projects, partnering with Mayors and local leaders, and developing new approaches to public service reform with a focus on experimentation and learning.”

“New approaches” are likely to be ‘mission-led’, ‘reform-focused’ and ‘technology-enabled’. On ‘mission led’ and ‘reform focused’ we are absolutely on the same page. On ‘technology-enabled’ we urge proportionality. Emotional intelligence has as much of a role to play as artificial intelligence in the public services of the future: Ministers must grip the science of relational offset, taking out relationships where they aren’t needed, and doubling down where they are.

‘Technology where it helps, relationships where they matter’ should be the mantra of the government’s new Office for Value for Money.

No step into the unknown

So a shift toward a more relational state involves investing more trust in the workforce and more confidence and more power in the community and it involves spending differently, but, importantly, it is not a step into the unknown.

We know that relationship-centred practice must play a big part in the public services of the future because we see it working already, although too often at the margins.

Take health care, for example, and the pressures on the NHS. 6% of UK adults are chronically lonely. That’s 2.5m people who are more likely to get sick than the rest of the population and less likely to have the support they need to recover at home.

The solution to overcrowded hospitals isn’t first and foremost in the hospital, it’s not even in digitalisation of health care, although it may make a contribution. It is in the community where effective relationships, carefully held and well connected to community practitioners, reduce admissions, speed up discharge and support sustainable social care

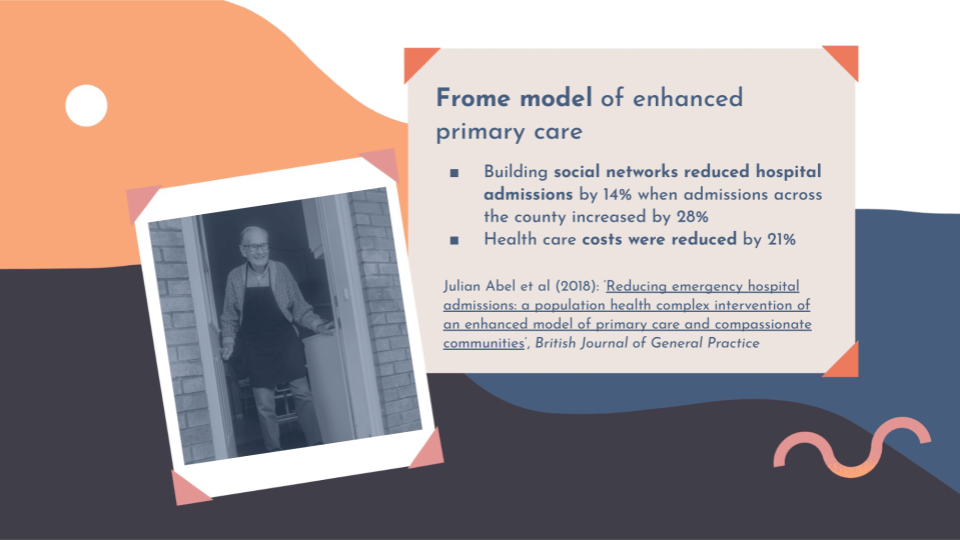

How do we know? Because in small projects, outside the mainstream, that future has already arrived. In Frome for instance, where targeted work on building social networks has reduced hospital admissions by 14% at a time when numbers elsewhere were increasing, and it cut costs.

Out of the ordinary

I remembered the allotment story last week not because it was extraordinary, but because it wasn’t.

It was ordinary people being there for one another, trusting one another, ‘doing what anyone would do’. They weren’t organised or enrolled or instructed, or for that matter checked and trained and monitored and measured. There was a degree of risk but, as in lockdown, the risk of an action must always be judged against the risk of inaction, weighing experience over edict.

It was social workers, a GP and practice nurse providing skilled sensitive care for a woman they knew. Trusted to steward a carefully calibrated relationship, not too little, leaving everything to the Big Society, not too much, confiscating agency from a strong woman.

And it was about a government, a local government, doing what it can do, setting budgets, determining priorities and planning allotments many years ago, understanding the importance of a social infrastructure and a built environment that enables relationships to breathe, to grow and to thrive.

A society of service, in every nook and cranny, built on good relationships.

Read part 2

In part two of this blog series, Rosa Friend draws encouragement and practical examples from the work of local authorities and their communities in the dark days of lockdown.

Related reads

Active Neighbours Field Guide

Covid-19 saw an outpouring of community-led support in which 9 million ‘volunteers’, stepped forward to help out. What are the stories behind these statistics? What’s needed to encourage and enable them to carry on caring? Our Active Neighbours Field Guide presents five Active Neighbour groups.

Relationships Case Maker

Few people argue that relationships don’t matter, but many feel they don’t have the time, capacity or permission to prioritise them. This Case Maker assembles the evidence base for putting relationships first, describing why relationships matter, what great relationship-centred practice looks like, and how it could make an impact in your context.