When we’re unwell, how does the compassion that healthcare workers give (or fail to give) shape our experiences and health outcomes?

In this blog, Rosa explores these questions, and shares two personal experiences that have shaped her thinking – (accidentally) giving birth at home and getting knocked on the head.

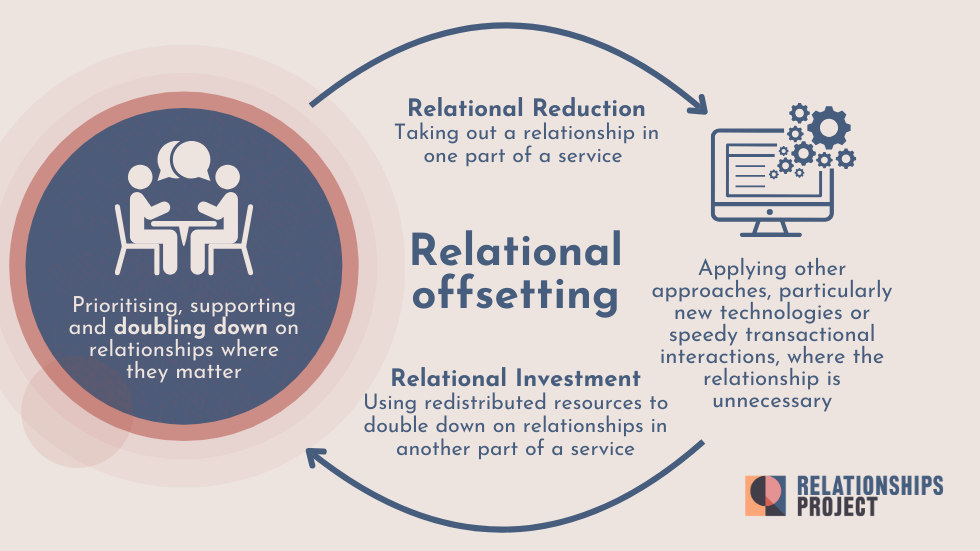

Could relational offsetting help ease the burden on our doctors and nurses, giving them space to listen, explain, and plug the communication gaps that can lead to inadequate care?

A collision

Last month, I was headbutted. I forgot about the collision soon after. The assaillant – my 19th-month-old daughter – seemed fine. I seemed fine. Just a mild headache.

I didn’t think about the knock until the next night when I woke with my head pulsing in pain. Paracetamol wasn’t touching the sides. Twelve hours later, nauseous, unable to move my head, hoping to be offered a more powerful analgesic, I called 111.

The nice man on the phone asked diagnostic questions. At the end of the call he said, “Based on what you’ve told me, you need to get to hospital in the next hour.” I pictured the hours on a hard chair waiting to be seen. I couldn’t even move my head a centimetre – navigating the south circular on the bus on a boiling day in rush hour? An insurmountable task.

“I’ve got to pick up my daughter soon. Is there any way I could just speak to a pharmacist?”

“You need to go to hospital.”

“Or an online consultation with a GP?”

“You need to go to hospital.”

At the hospital

Arriving there, head throbbing, bile whisking up my throat, my bag was searched by a security guard. I queued to speak to someone behind a glass screen.

“And you say your baby headbutted you. How is she? And why haven’t you brought her with you too… if it was such a hard whack?”

Why hadn’t I? Why had I thought more about myself than her? Was she feeling as bad as I was, just unable to express it? After I described my symptoms, just as I had for 111, the man behind the glass said, “This is a matter for the GP.”

I wished the man could open up the notes from 111 – see I’d already answered all these questions, see it wasn’t my idea to be here.

“This isn’t a matter for urgent care,” the man behind the glass said.

I was embarrassed that I was now crying. It wasn’t at the current situation, exactly, or not just that – it was wrapped up in something else.

Needing to push

The last time I had been there, at the hospital, it was the day I gave birth to my daughter. I arrived in an ambulance, holding a newborn child. She had been born at home (not the plan) with no medical professional present (definitely not the plan).

How could that happen, people have asked me since. Seven hours into contractions, I was in the bath and I felt something in my body change. A peculiar, powerful, primal feeling: I needed to push. My boyfriend called the midwife, to ask if we could come into the birth centre at the hospital.

I wasn’t sure if I was cut out for labour when I heard what the midwife said:

“It’s a marathon not a sprint; tell her to stop screaming, take deep breaths, conserve her energy. You’re not ready to come in. She’ll know when she’s ready to come in.”

I thought I knew I was ready but I had not done this before.

I tried to stop myself from pushing, but my body had other ideas. 20 minutes later I said to my boyfriend, “There’s something coming out.” What it was – organ, bodily fluid, tiny human – I wasn’t sure.

“It’s a head. I think it’s a head.” He had called the midwife again. “It’s happening,” he said.

“You think it’s really time to come into the hospital?”

“It’s too late for that. It’s happening. Now.”

A case for compassion

The man behind the glass saw my tears and decided actually I could enter Urgent Care. I was embarrassed to have cried, I wanted to explain what was going on in my head, the midwife, the pushing, but it felt too complicated to explain the backstory. He was already calling the next person in line forward.

An hour later, I was seen by the triage nurse. Four hours later, a doctor saw me. She had read my notes and didn’t make me repeat what happened. Instead she took a moment to look me in the eyes and said, “Knocks to the head are horrible. How are you doing?” After an examination: “You have a concussion and you’re going to need to take it easy. But I see from your notes you have a toddler – so I get that’s probably an impossible task.”

I had recently read research from Trzeciak and Mazzarelli which found that when healthcare providers demonstrate compassion, medication adherence increases by 80% and healthcare spending reduces by up to 51%. In this moment, the interaction with the doctor, feeling understood and cared for, I felt it for myself – the transformative powers of compassion.

A case for relational offsetting

I share these two stories of being turned away – or almost turned away – not to blame anyone but because the man behind the glass, the midwife down the phoneline and the doctor in A&E do such important jobs. Such difficult jobs. Their days are always going to be hard – dealing with death and birth and pain and people – but could we design organisational conditions and put support in place that make them a little easier?

This doesn’t need to take more time or cost strapped services more money. At the Relationships Project we’ve been exploring the idea of Relational Offsetting – or taking a human-to-human interaction out of one part of a service and using the resources to double down on relationships in another, where they matter.

All the people in the queue ahead of me at the hospital had also been sent by 111. All answered 10 minutes of questions that they had already answered by 111 advisors. How much time would the NHS save if the 111 notes were transferred through to the hospital? This conversation with the man behind the glass wasn’t the triage; it was just an exchange to grant permission to enter the hospital department. This is designing a long interaction into a process where some transactional tech functionality – sharing notes securely – would not only be more efficient but also result in less frustration for people in pain. The time recouped could be spent giving healthcare professionals permission and space to offer compassion, as the A&E doctor did so beautifully – so humanly – in less than a minute.

111 and the art of gatekeeping

111 is in itself a form of relational offsetting: a way for the NHS to manage demand and focus clinicians’ face-to-face time where it is most needed. To manage these calls, call handlers use NHS pathways, essentially a series of algorithms that link clinical questions and care advice. Healthcare is complex and nuanced – your pain threshold may well be higher than mine – so it is difficult for either humans or algorithms to get right all of the time. But Healthwatch research from 2021 showed that 72% people had generally positive experiences when they called NHS 111, suggesting that most of the time it is getting it right. As we might predict, those who weren’t offered time with clinicians were less likely to feel satisfied.

How could the experience be improved for those people? Is there something to be said in how call handlers and receptionists redirect people? Done badly, it can lead to conflict and recrimination. Done well, we feel that we are heard, respected and treated fairly, even when we don’t get seen by a doctor.

Vital relational skills

What about the accidental home birth? Are there things that could have been put in place to prevent that happening, to have saved the cost of two ambulances, four paramedics? I felt I was ready to come to the hospital, my body was telling me it was time to push, I was trying to articulate that… and yet I also felt inexperienced. The midwife was saying something else and knew better.

I’ve since heard of other people who have had similar experiences: my friend was also turned away, my cousin’s girlfriend had her baby in the car.

Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett writes, “often it seems a traumatic birth is characterised by communication gaps.” One study suggests a third of new mothers are traumatised by childbirth. For Black women, the picture is bleaker still. The Black Maternity Experiences report, published July 2025, describes “poor communication, lack of empathy and unequal power dynamics leaving Black women feeling unsupported and unsafe.”

Relational skills could transform how we live and work together. Listening well is a skill that can be taught, a vital skill. But any training must include an examination of our biases and the power dynamics which affect how we interact with one another.

Into action

I was lucky. Though I didn’t feel listened to when I wanted to go into hospital, I remember, after the midwife understood that the baby’s head was already out, how she snapped into action, asking clarifying questions down the phone. She was brilliant. Calm and clear as she coached us – clueless –in how to deliver a baby. I remember my boyfriend somehow mirroring the midwife’s calm as he described that there was an umbilical cord round the neck, our baby was unresponsive. The midwife giving more instructions, my boyfriend carefully unwrapping the umbilical cord, an excruciating wait, then, the baby crying, the best sound there ever was, moving us from the lowest low to the highest high, the midwife ecstatic too, on the other end of the phone.

Medical professionals deal with nerve-wracking situations, far more challenging than what I’ve described happening to me, day in, day out. They get up over and over to do it again, but the training they’re offered and the processes and systems they’re working within don’t have to stay the same. We owe it to them, to each other, to push for another way.