In brief

In this Joining the Dots blog, Immy Robinson – Research and Innovation Lead at Shift and co-lead of The Relationships Project – explores some of the knotty questions around measuring and evaluating relationships.

The need for measurement

The importance of data in decision-making across all sectors is widely established. Measuring progress towards set goals is essential for learning, improvement, buy-in and decision-making, but some things better lend themselves to measurement than others.

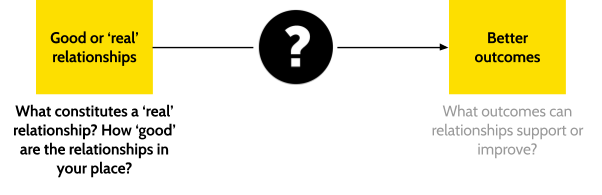

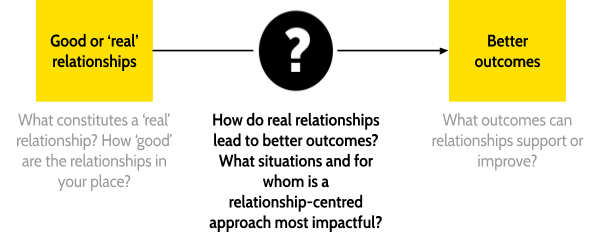

From a field-building perspective, evaluating relationships feels essential. We need to know why relationships are important, how they add value, which situations benefit most from a relationship-centred approach, what types of relationships add value, and what a ‘good’ relationship looks like, amongst other things. Some of these things are easier to assess than others.

When it comes to taking a relationship-centred approach, this raises the question: what can and what should be evaluated?

This blog is a very initial attempt at exploring this question. Much more thinking and discussion will be required.

Measuring relationships outcomes

Measuring the impact of relationships on specific outcomes is conceivable and doable. Which outcomes we focus on will be determined by the specific place in question: for the supermarket, a relationship-centred approach must contribute to financial returns, for a but for a community initiative, relationships may be an end in themselves, contributing to a more connected community.

Studies using control groups or baselines alongside existing measures tracking an organisation’s ‘bottom line’ (health outcomes, value for money, GCSE results, profits, staff retention etc) can help us to understand – and build a stronger evidence base for – the value of investing in a relationship-centred approach.

But focusing solely on measuring the outcomes of relationships is problematic for a couple of reasons:

- It doesn’t tell us about the inputs (i.e. what constitutes a ‘good’ relationship) or the process (how relationships lead to better outcomes), just the outcomes themselves

- It risks treating relationships as a means to an end, rather than an end in themselves

Assessing the quality of a relationship

To piece together more of the puzzle, we need to know more than just the outcomes of a relationship-centred approach; we need to also know something about the inputs and the process by which inputs are translated into outcomes.

If a school, a GP practice, a company or a council were to invest in a more relationship-centred way of working, it would be reasonable to expect that they would want to be able to assess the state of their key relationships in order to see whether they’re on track to deliver the outcomes that matter in that place. But there are a few things to consider before we jump in and measure relationships themselves.

1. Ethical considerations

Firstly, when it comes to the question of assessing relationships, there’s an ethical question that we need to consider: should we assess relationships?

What are the potential risks of doing so? Could assessing a relationship damage it by compromising the intimacy that sits at its heart?

Could developing a measure or set of measures for relationships skew us to a more standardised definition of a relationship, and in the process risk transactionalising them?

Measurement can have unintended consequences. We must embrace this challenge with eyes wide open, making sure that in our pursuit to build our understanding of – and a case for – a more relationship-centred way of working, we do not damage the very essence and power that relationships hold.

2. Practical considerations

Secondly, there are practical considerations around the feasibility and utility of assessing relationships.

Relationships, by their very nature, are emergent, dynamic, personal, idiosyncratic, uncontrollable. This is what makes them different from a process. Consider these two examples:

I call up to dispute a bill with my energy provider. I’m passed between telehandlers in different departments. Each follows a rigid, impersonal script. I’m interacting with a process, not a relationship. There’s no warmth, no personal connection, no adapting to my specific situation. I leave the call angry and frustrated.

My grandma has just passed away. I call my friend. We usually have a jokey, boisterous, lightly mocking relationship. She senses the sadness in my voice and offers a sympathetic ear, a warm hug. This is a real relationship. It adapts to the situation. It’s personal between two people. I’m comforted, and we become closer.

Measuring something that is ever-changing, deeply personal, and highly context specific is challenging. Standardised measures are unlikely to capture the complexity of individual relationships. Perhaps the best we could hope for is a snapshot of that relationship, assessed via self-reports (How satisfied are you with this relationship? To what extent do you feel supported / valued etc within this relationship? To what extent do you feel this is a trusting relationship? etc).

But we have seen in the arena of marital research that self-reports can be unreliable predictors of longer-term outcomes (in this instance, divorce). Observable behaviours – such as whether partners respond to each other’s bids for attention – are arguably more accurate in predicting whether divorce is on the cards.

The need for empirical research

To advance our understanding of how, in which circumstances and under what conditions relationships can lead to better outcomes, more empirical research is needed. If we start with a hypothesis about what constitutes a ‘good’ relationship and are clear about the outcomes we’re trying to drive towards, empirical research can help us to understand more about what processes, behaviours, contexts etc help to translate these inputs into outcomes. This will help to advance our understanding of how a more relationship-centred way of working best operates, and build a stronger case for it.

Moving the conversation along

Whilst this blog has attempted to tease open some important questions, there’s much more to explore. For example:

- Should we talk about ‘measuring’ relationships, or are assessment or evaluation more appropriate terms? Evaluation suggests a more resource-intensive approach which may put some stakeholders off, but ‘measurement’ feels antithetical to the nature of relationships.

- Should we be concerned with developing a consistent approach to measuring / assessing / evaluating relationships across sectors, places, and topic areas? We believe that there’s much that can be learned from one another in the field of relationship-centred design, but could pursuing a consistent approach to evaluation over-complicate things?

- This blog briefly touches on the field of marriage counselling. What other sectors or topic areas can we learn from as we embark on the challenge of evaluating a relationship-centred approach?

Please do share your thoughts by leaving a comment below, tweeting us @shift_org or getting in touch with immy.robinson@shiftdesign.org