In brief

In this important and moving piece, David Grayson examines the caring relationship and proposes a “new social contract for carers and caring.”

David Grayson

CEO at Central YMCA

David Grayson CBE is chair of the charity Carers UK which works for a society which respects, values and supports carers. He is a serial social entrepreneur and is Emeritus Professor of Corporate Responsibility at Cranfield School of Management. Amongst his numerous books is “Take Care: How to be a great employer for working carers” (Emerald 2017). He was the first (and only) chair of the National Disability Council – appointed by Parliament to fight discrimination against Britons with disabilities.

David would like to hear more ideas for the contents of a new Social Contract for Caring | www.DavidGrayson.net | @DavidGrayson |

Part of what it is to be human

Caring is part of the rhythm of life. It is part of what it is to be human – because relationships matter. Rosalynn Carter – wife of the former US President Jimmy Carter – has observed that there are only four types of people: people who are carers, people who have been carers, people who will be carers – and people who need to be cared for. Many of those will be all of those at different stages in their lives. I know I have.

For many of us, caring may prove to be the most profound thing we do in our lives. Certainly, for me, making sure that my mum could spend her final years as she wanted, safely and happily in the family home, is almost certainly the most important thing I will do in my life.

I wanted to do it anyway, but there was also a sense of repaying a debt. My mum hadn’t just nurtured me, but also nursed me through a life-threatening and disabling bone-disease when I was eleven. Then once I had recovered sufficiently, she rushed back to teaching so that she and my father could afford to pay the school fees for a private school, near where we lived, that would look after me as I learnt to walk again and regain my independence.

But caring can profoundly change relationships

We care for one another. Yet in becoming a carer: for a parent, a husband or wife, a disabled sibling or child, a good friend or neighbour, relationships often change.

“I am not my husband’s carer!” one lady indignantly declared: “I am his wife!” And yet, she had indeed become his full-time carer – and that often squeezes out the original relationship.

If you watched the recent two-part, BBC Panorama TV programme: Care in Crisis, which examined the challenges facing Adult Social Care in Somerset, you will have a good idea of what I mean. Presented by reported Alison Holt, Panorama had extensive access to the deliberations of Somerset County Council as they desperately tried to navigate the competing demands of austerity and cuts in central government funding on the one hand, and on the other, the complex needs of a rapidly ageing population.

As I chair the charity Carers UK, it is perhaps not surprising that in watching the programme, I was particularly focused on the impact of savage spending cuts, on individual lives: both of people being cared for, and even more of the family and friends on whom more of the caring burden fell, as paid care was ferociously rationed.

Although I am a Yorkshire man of a certain age, I don’t mind admitting that I alternated between empathy, anger on their behalf, tears of frustration, and a fierce impatience for Carers UK to intensify our efforts to promote a society which truly respects, values and supports carers.

We saw the husband of a severely disabled woman, exhausted by the 24/7 demands of looking after his wife round the clock, bringing up their triplets and being the bread-winner too. We saw the middle-aged daughter looking after her elderly mother with advanced Alzheimer’s, whose two days of respite per week whilst mum visited a day-care centre, were brutally removed, when the Council had to close the centre. We saw the 60-year-old with Downs Syndrome and severe learning disabilities, who had been looked after by his mother until her death, whose family struggled to persuade the Council to fund a suitable care- home. We saw the wife looking after her husband, who had become severely disabled.

We also saw the social workers, the Occupational therapists, the district nurses, the care- workers, the council managers and elected members as they struggled to do their best for those needing support.

A catalyst for change?

I am just old enough to remember the profound impact of another television programme: “Cathy Come Home,” on the country’s attitudes to homelessness, fifty years ago. I truly hope that the Panorama documentary will prove to be a similar “wake-up” call to our politicians, to secure cross-party agreement on a long-term funding settlement for social care. Without it, there will be many more carers, like the unseen lady calling in to Somerset Social Care, who could simply no longer care for her incontinent husband: “He is in hospital now. When he comes out, I don’t want him home.”

Many long-term, long-hours carers are at the end of their tethers. Without respite care and adequate support, it is not being alarmist to predict that propensity to care will decline – substantially.

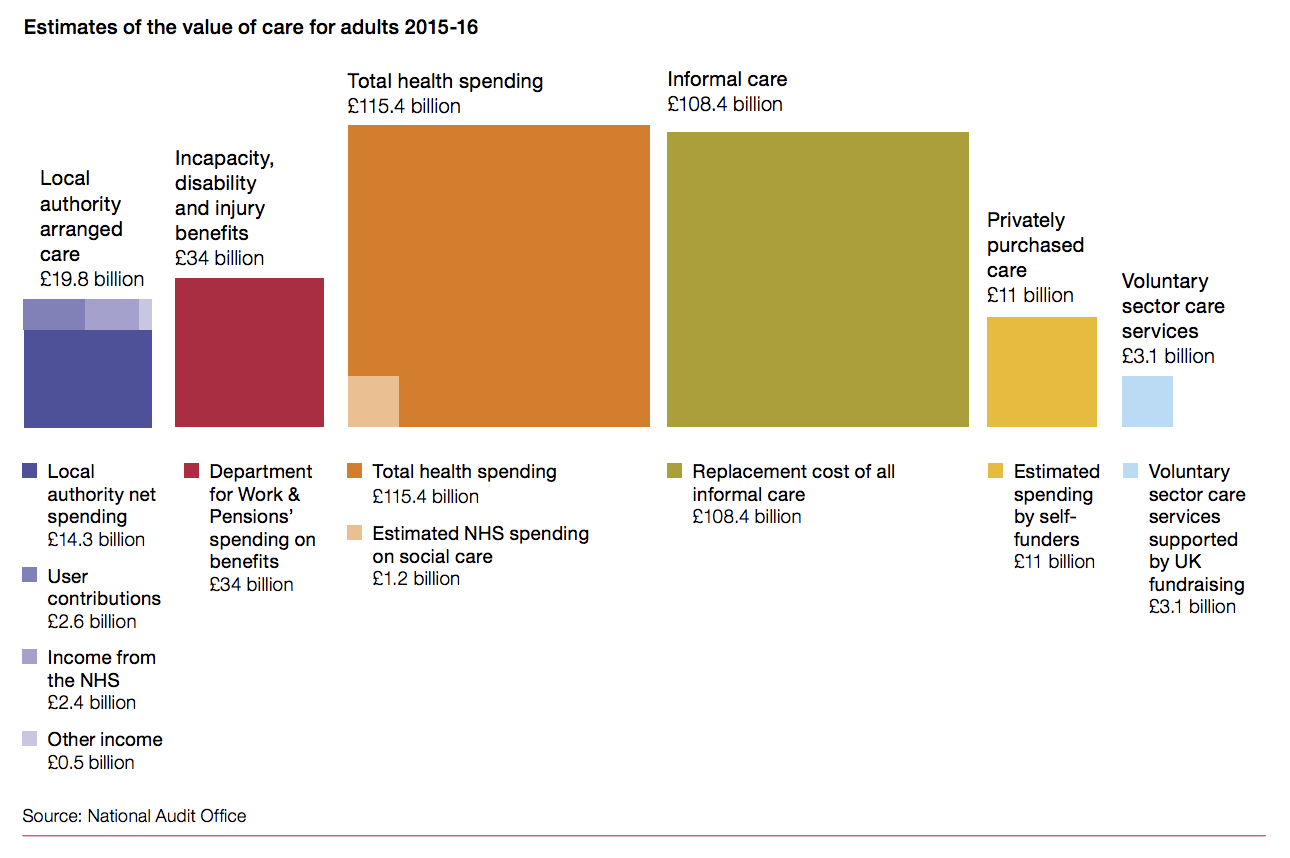

Yet sufficient publicly-funded social care is only one element of a new Social Contract to support families and friends caring for loved ones. This is vitally important because – as the National Audit Office has shown (see chart below), public and privately funded social care is dwarfed by the contribution of unpaid caring by family and friends.

Source: A Short Guide to Local Authorities by the NAO

Most of us care because we want to. We love the person we are looking after. Caring can bring great joy. Yet we know it also often comes at great cost: in financial pressures (particularly if the carer has to give up work to look after their loved one); in social isolation and loneliness; in physical and mental ill-health – and even sometimes, in relationship break-downs.

A new social contract for carers and caring

A new Social Contract for carers would address these negatives.

1. Employers

Employers would be Carer Confident. They would support the 1:7 of their employees juggling job and caring, to stay in work – or to return to work at the end of their Caring Journey. Employers would offer flexible working, encourage networks for mutual support amongst their working carers and paid Carer’s Leave.

2. The NHS

The NHS would identify carers and be proactive in helping carers to look after their own health. Think of the airline safety demonstration: “fit your own oxygen mask before helping others.” The NHS would fully involve carers in discussing options for the person being cared for and recognise carers as a vital source of knowledge about patients especially frail and elderly patients. Thanks to the awesome determination of the John’s Campaign, most hospitals in the UK now allow carers of patients with dementia to stay with them, irrespective of visiting hours. That is recognising that often, carers are the primary health care.

3. Funding

A new Social Contract would establish a generous Carer’s Allowance for long-term, long hours carers, would ring-fence sufficient funds to allow intensive carers to have time-off and Carer Breaks – and would fund effective Public Information campaigns to ensure that everyone eligible would apply for and receive Pension Credit for their time out of work to care for their loved one.

4. Collaboration

Government, local authorities, charities, Citizens’ Advice Bureaux, faith groups, trade unions and employers would “join the dots” to ensure that people are “Caring-prepared” able to recognise the tell tale, early signs of when they – or someone they know – is becoming a carer. Often, it creeps up on us, unexpectedly and imperceptibly. Knowing this is likely to happen to us at some stage(s) in our lives, remembering the search terms to find relevant information quickly, and being able to access support groups/ Carer befriending services to talk through what we are feeling, could make carers just that bit more resilient.

As the chair of a carers’ charity, I realise I am biased, but I passionately believe that a new Social Contract on caring would also provide substantial Challenge Grants to encourage social enterprises, voluntary organisations and the public and private sectors, to form cross- sectoral partnerships to improve Advice & Information (A&I) and support services to carers. This might make it easier, for example, to facilitate joint provision between condition- specific health charities like Alzheimer’s and carers’ charities where the former concentrates on A&I on the specifics of caring for a person with “their” condition, whilst signposting to Carers’ groups for generic information about being a carer.

Nurturing relationships

There came a time in my own Caring Journey, when – in order for her to continue living in the family home – mum needed a 24/7 live-in care-worker. We were fortunate. We could afford to pay, and we found an incredibly dedicated and patient lady: Ann, who helped to look after mum for the final thirteen months of her life. Afterwards, Ann spoke of my mum as being like a second mum to her. Apart from anything else, for me, it meant in those thirteen months, I could be more of a son again. My weekly visits were no longer about the shopping and so on, but spending time with mum, reminiscing over old family photos and scrapbooks and the like.

In recent years, our politicians have repeatedly told us that we live in one of the richest countries in the world. Surely one of the benefits of living in such a country, should be that we have the resources and the wherewithal to ensure that we can be both carers and nurture our relationships at the same time.