In brief

In this contribution to Joining the Dots, Toby Lowe and Dawn Plimmer discuss funding, commissioning and managing services in a world where relationships rather than KPIs or simplistic numerical targets are what matters most.

Toby Lowe

Senior Lecturer at Northumbria University

Toby is is a Senior Lecturer in Public Management and Leadership at Newcastle Business School, Northumbria University. Previously, Toby has worked in both the voluntary and public sectors. You can contact Toby at toby.lowe@northumbria.ac.uk

Dawn Plimmer

Head of Practice at Collaborate

Dawn is Head of Practice at Collaborate, a social enterprise that helps organisations and communities work better together to tackle complex social challenges. She has worked for a range of UK and international funders and is passionate about making funding work better for those it seeks to support. You can get in touch with Dawn at dawn@collaboratecic.com.

The reason we’re doing this work is because we’ve seen first hand the failure of New Public Management (NPM) approaches, based on target-based performance management, to effectively support and improve public and voluntary sector practice in complex environments.

Wherever you go in the UK, when you talk with those doing social action you will hear stories of NPM approaches wasting precious resources, and sapping the motivation of those forced to work under their auspices. You don’t have to dig far to find multiple examples of NPM having a devastating impact on people’s lives.

Why does this happen? Because NPM is designed for a world that is simple and linear. A world in which problems have known solutions, and which if you do X, then Y happens.

In those circumstances, it can be sensible to set targets, or have Key Performance Indicators based around sticking to known processes.

But the world of social action, in which the public and voluntary sector operates, is mostly not like that. The world of social action is often complex.

We know that social action is complex because:

- there are a variety of strengths and needs amongst those we serve, and these look different from different perspectives

- the outcomes people desire are produced by many factors interacting together in an ever

changing way - people are working in systems that are beyond the control of any one of the actors in the

system

In the words of one of the organisations we worked with, this requires us to “embrace the mess to do what’s best for people, not what’s comfortable.”

Embracing complexity demands a different form of management. (This is exactly what the research evidence tells us). As leaders and managers, and those who support them, we can and must do better.

This is why we have been seeking to learn from those who are trying to do better, and help to share that practice. This is why we think that the Human, Learning, Systems approach which we have uncovered is important.

What does the Human, Learning Systems approach involve?

1. Human

One of the three key tasks of managing work in an HLS way (including funding and commissioning of work) means creating the conditions in which people can build effective human relationships.

This means understanding human variety, using empathy to understand the lives of others, recognising people’s strengths, and trusting those who do the work. Variety, Empathy, Strengths and Trust (VEST).

To make this shift, Mark Smith, Director of Public Service Reform at Gateshead Council (one of the case studies featured in our latest report) talks of the need to ‘liberate’ workers from attempts to proceduralise what happens in good human relationships, and instead focus on the capabilities and contexts which help enable these relationships.

2. Learning

In complex environments people are required to learn continuously in order to adapt to the dynamic, ever-changing nature of the work. In complex environments, there is no simple interventions which “works” to tackle a problem. “What works” is an on-going process of learning and adaptation.

It is the job of managers to enable staff to learn continuously as the tool for performance improvement.

This means using measures to learn, not for reward/punishment. It means creating the conditions where people can be honest about their mistakes and uncertainties. It means creating reflective practice environments between and across peer groups.

This requires funders/commissioners to fund for learning and adaptation, not for “results”.

3. Systems

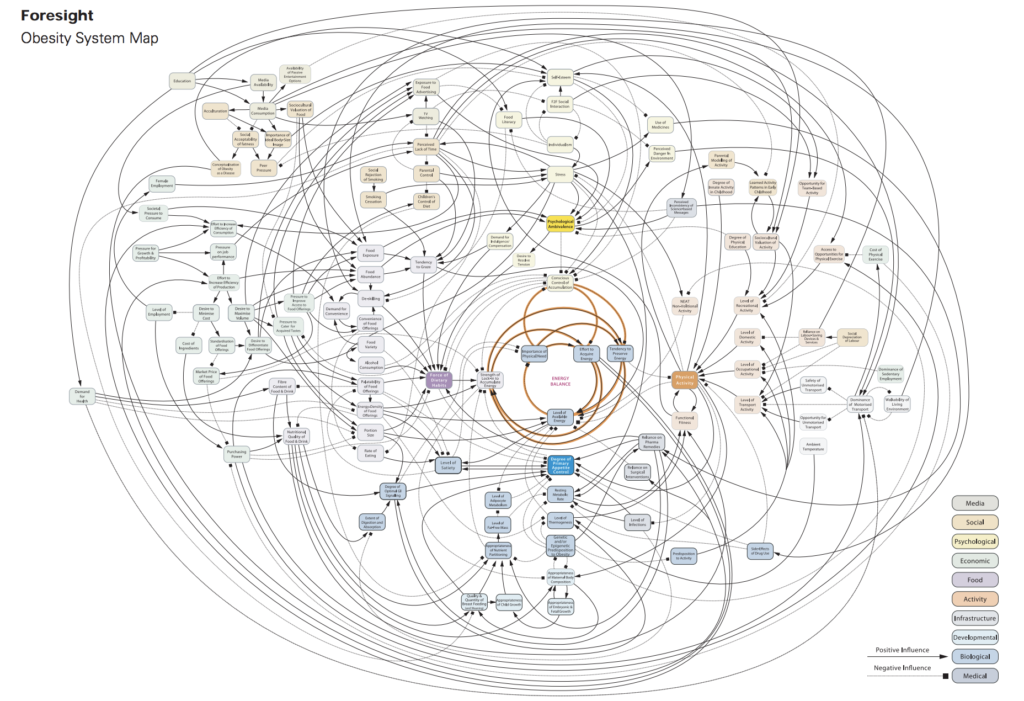

The outcomes we care about are not delivered by organisations. They are produced by whole systems – by hundreds of different factors working together (as can be seen from this systems map of obesity):

Source: Government Office for Science 2017

The final job of managers is therefore to act as Systems Stewards – to enable actors in the system to co-ordinate and collaborate effectively – because this is what will enable positive outcomes to emerge.

You can read more about the detail of the HLS approach here.

Examples in practice

The report has a series of case studies which shows how the approach is being used in practice.

For example, it is being used by public sector commissioners in Plymouth (where they have just commissioned an £80m 10 year system of support for vulnerable adults with no KPIs or output/outcome targets – they have built an effective learning system of organisations, and are holding them accountable for working together and learning).

It is being used by funders such as The Tudor Trust and Lankelly Chase to build relationships of trust with those they support, and those organisations to learn, and to share learning.

It is also being used by Mayday Trust and Cornerstone as a way to build relationships with, and respond to the individual strengths and needs of, the people they support.

Building a Movement for Human Learning Systems

The enthusiasm for this way of working has been incredible. The report was downloaded over 2,000 times in its first week of release. Over 250 people signed up for the launch events we held in Newcastle and London last week, and there are more than 260 people part of the digital Community of Practice which has formed around this approach.

We want to make HLS practice a perfectly normal choice for funders, commissioners and those who manage public and voluntary sector work.

How will we do that?

We’re seeking to build the capacity for collective action to make this happen. We engaged the 200 organisations who attended the launches of the report in conversation about how to create the collective action for change. This has helped to shape some key ideas for the HLS movement:

Build the “collective bravery”

Create networks of “nerve givers” who can support one another

Get people speaking the language

Watch out for co-option, but don’t be precious. Learn in public.

Create an enabling national context

Help shift the political dialogue. Emphasise the human. Help regulators to behave differently.

Enable local collaboration and experimentation

Create spaces for shared learning. Create the right environment for honest dialogue. In the words of one of our partners, develop the conditions to “infect others like fungus!”

Promote Organisational Change and skills development

Help to develop system leadership capacity and happy fulfilled workers – “the fear-free organization”

Widen involvement in the movement

Make it accessible to everyone and get more people contributing ideas and practice. Get more funders on board.

Promote Learning about HLS practice

Collect evidence. Tell the different stories of HLS practice – talk about the different starting points. The movement must be an example of itself – let’s learn in public.

How to join in

If you’d like to join in, here are some things you can do straight away.

1. Champion the approach

Share the report with people, ask why things can’t be different

2. Connect with others

The movement will grow by people developing a sense of “collective bravery” and sharing their practice and experiences with one another. Join the online Community of Practice here.

Start (or join) a group locally who are talking about how to do this. Hopefully, we’ll soon have an interactive map showing where the groups are, but in the meantime, drop us an email, and we’ll try to connect you up.

3. Hold people to account for using failing NPM approaches

There is overwhelming evidence that the NPM approach fails in complex environments. If you recognise your environment as complex, ask people who are choosing to fund, commission or manage in NPM ways (creating competition rather than collaboration, specifying work using targets/KPIs etc) why they have made that choice. Ask them to back that choice up with evidence. Ask them to consider the implications for people’s lives.

Together we can change how we fund, commission and manage social change in a way that works for the 21st Century. Are you in?